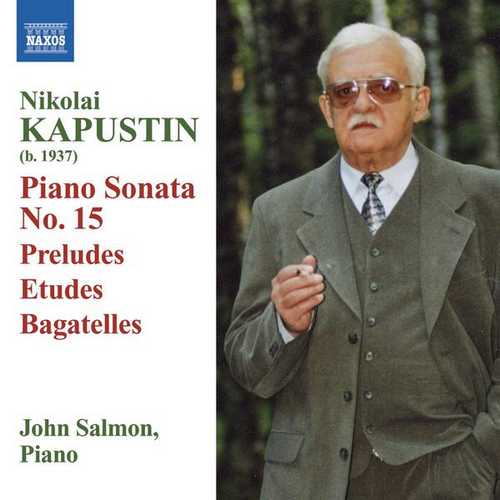

Composer: Nikolai Kapustin

Performer: John Salmon

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: Naxos

Catalogue: 8570532

Release: 2008

Size: 164 MB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: yes

Piano Sonata No. 15, Op. 127 – ‘Fantasia quasi Sonata’

01. I. Maestoso – Allegro assai

02. II. Grave

03. III. Sostenuto – Allegro scherzando

04. IV. Allegro rigoroso

24 Preludes in Jazz Style, Op. 53

05. Prelude No. 11 in B major

06. Prelude No. 12 in G sharp minor

07. Prelude No. 13 in G flat major

08 .Prelude No. 17 in A flat major

09. Prelude No. 18 in F minor

8 Concert Etudes, Op. 40

10. Etude No. 5, “Shuitka” (Raillery)

11. Etude No. 6, “Pastoral”

12. Etude No. 7, “Intermezzo”

10 Bagatelles, Op. 59

13. Bagatelle No. 2

14. Bagatelle No. 5

15. Bagatelle No. 8

Piano Sonata No. 2, Op. 54

16. II. Scherzo

Kapustin’s pianistic textures are rich, spanning the entire keyboard, with melodies in every register, sweeping arpeggios, tons of chords, and a fantastic array of runs. Such music is Kapustin’s birthright: Ukranian born and Moscow trained, he has Medtner, Rachmaninov and Scriabin in his veins. But the jazz side is equally authentic, incorporating the fleet pianism of Oscar Peterson and the harmonic volatility and technical exuberance of Art Tatum. Kapustin’s music also encompasses more modern sounds, such as McCoy Tyner’s quartal voicings and the pop-tinged stylings of Keith Jarrett.

Nikolai Kapustin is a name unknown in the West until the turn of the twenty first century, and this in itself is none too surprising, as Kapustin has stated that he “does not want to become famous.” A one-time student of Moscow Conservatory pedagogue Alexander Goldenweiser, since the late ’50s, Kapustin has been turning out an impressive portfolio of jazz-inspired compositions, including six piano concertos, a fantasy of piano and orchestra, and numerous solo sonatas and preludes. Kapustin does not like to improvise and disdains live performances — both prerequisites in conducting a career as a jazz pianist — so his solution was simply to write everything out. His works were published one after another even in the Soviet period, and Kapustin claims that he has made a good living from it. The emergence of interest in his work outside Russia is something that seems a little befuddling to him. However, the music publishing industry in Russia that once supported his efforts has collapsed along with all Soviet-bred institutions, so Kapustin at least welcomes the additional interest.

Pianist John Salmon, a classical pianist who has recorded the music of Dave Brubeck in some depth, is an ideal candidate for interpreting Kapustin as his past efforts ensure that the learning curve in terms of projecting rhythm and an idiomatic sense of pace is not going to amount to much, if anything. Kapustin’s Piano Sonata No. 2, Op. 54 (1989), has been an early one out of the gate in attracting the attention of pianists, already recorded three times, but Salmon includes only the second-movement Scherzo here. The main work included is a very new one at the time of release, the Piano Sonata No. 15, Op. 127 “Fantasia quasi Sonata” (2005-2006). It is quite ambitious; the fourth-movement Allegro rigoroso is a continuous torrent of notes spinning out jazzy phrases from beginning to end, so dizzying in pace and in its flow of ideas that a principal idea — indeed, if there is one — eludes the ear. Nevertheless, it is a good ride, sort of like being on a jazzy roller coaster that is coming close to flying off the tracks.

The balance of the disc is taken up with individual movements selected from Kapustin’s large collections of short pieces, the 24 Preludes in Jazz Style, Op. 53 (1988); the 8 Concert Etudes, Op. 40 (1984); and his 10 Bagatelles, Op. 59 (1991). They show a remarkable range of ideas; the Prelude No. 13 in G flat definitely utilizes the “Take Five” rhythm associated with Brubeck, whereas No. 11 in B is bluesy, No. 12 in G sharp smacks of the tango, and so on. All of these pieces — without regard to the inherent nature of the various popular forms that Kapustin draws upon — seem informed by a deeply personal language that has its roots in the Russian piano school to which Kapustin is a natural heir — Rachmaninoff, Scriabin, Medtner, and others. There is an equal investment in that relative to Kapustin’s use of jazz, and while this might tend to rob Kapustin’s music of its jazziness, he insists he is not a jazz musician at all, but a classical composer, period. Indeed, Kapustin’s music is an accomplished, and highly virtuosic, synthesis of both. While Steven Osborne’s 1999 recording of Kapustin’s music has rather set the pace for the dissemination of his work in the West, this Naxos effort from John Salmon seems ideal, in its range and scope, for introducing the rarefied music of Kapustin to newcomers. Salmon’s interpretations are accomplished and idiomatic, and while one might have wanted a bit more presence for the piano in the recording, it is still better than adequate.