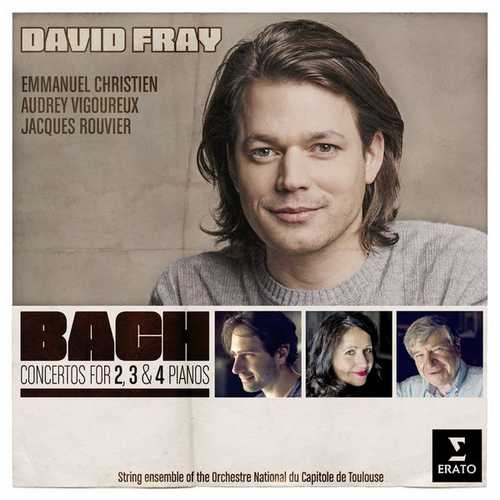

Composer: Johann Sebastian Bach

Performer: David Fray, Jacques Rouvier, Audrey Vigoureux, Emmanuel Christien

Orchestra: Orchestre du Capitole de Toulouse

Conductor: David Fray

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: Erato

Catalogue: 9029563228

Release: 2018

Size: 1.25 GB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: yes

Concerto for Four Keyboards in A minor (after Vivaldi), BWV1065

01. I. Allegro

02. II. Largo

03. III. Allegro

Concerto for Three Keyboards in D minor, BWV1063

04. I. Allegro

05. II. Alla Siciliana

06. III. Allegro

Concerto for Two Keyboards in C minor, BWV1062

07. I. Vivace

08. II. Largo ma non tanto

09. III. Allegro assai

Concerto for Two Keyboards in C major, BWV1061

10. I. Allegro

11. II. Adagio ovvero largo

12. III. Fuga

Concerto for Two Keyboards in C minor, BWV1060

13. I. Allegro

14. II. Adagio

15. III. Allegro

The music on this album gives rise to two intriguing questions. Firstly, are these concertos original Bachian creations? Secondly, should they be played on modern pianos. The two issues are in fact closely linked by the idea of transcription.

Four of the keyboard concertos recorded here derive either from works originally composed by Bach for other instruments (this is true of the Concerto in C minor, BWV 1062 for two harpsichords – a transcription of the celebrated and exceptional Concerto in D minor for two violins, BWV 1043), or from works by Bach of which we are more or less aware, but whose initial versions have not survived. This applies to the Concerto in C major, BWV 1061 and the Concerto in C minor, BWV 1060. As for the Concerto in A minor, BWV 1065 for four harpsichords, it is a reworking of the tenth concerto from Vivaldi’s L’Estro armonico, op.3, for four violins.

This is certainly a Bach reading that leans toward the old school: not only are pianos used, but there’s a good deal of pedal that produces rather Chopinesque slow movements. Sample that of the Concerto in A minor for four pianos, BWV 1065, to see whether you find the approach at all sympathetic; 50 years ago it would have been simply normal Bach performance, especially given that the String Ensemble of the Orchestre National du Capitole de Toulouse, like the first wave of Italian Baroque orchestras, is slimmer than the symphony orchestras that brought Bach down from the Romantics. If you are down with it, you’ll find performances here that are enjoyable in many ways. These concertos were all transcribed from other works, including in one case (the four-piano concerto) a concerto for four violins by Vivaldi. The talents of lead pianist and director David Fray are well-suited to this aspect of Bach’s genius: Bach fools with the texture of the originals, and Fray’s playful, varied attacks draw attention to what’s happening. Another attractive feature is that the four pianists involved make up, in Fray’s words, “a family affair”; Fray, Audrey Vigoureux, and Emmanuel Christien were all students of the fourth player, Jacques Rouvier, at the Paris Conservatory, and the interchange among the players in all these concertos is lively and unforced. The downside here, and it’s major, is the sound: the Carmelite Chapel in Toulouse is a lovely structure, but acoustically it bears little resemblance to the domestic settings for which these concertos were made, and in the Concerto for four pianos it produces little more than a Spectoresque Wall of Sound. In the pair of two-piano concertos, you are a bit more able to hear what’s going on. Even with this drawback, this is an enjoyable Bach concerto recording.