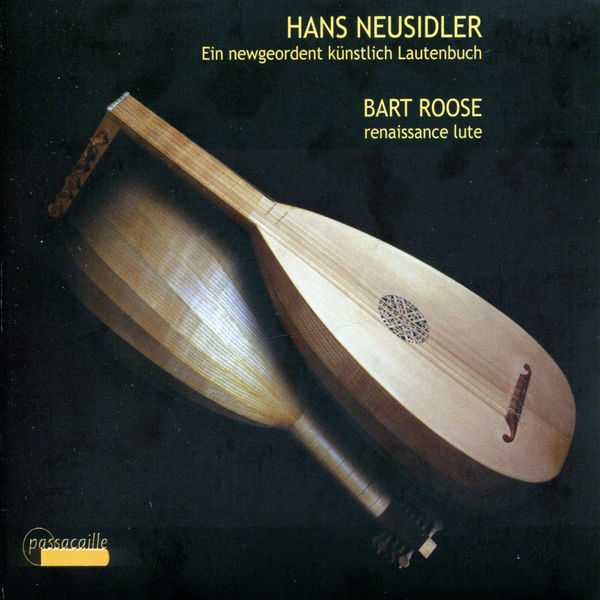

Composer: Hans Neusidler

Performer: Bart Roose

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: Passacaille

Catalogue: PAS945

Release: 2008

Size: 286 MB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: cover

01. Ein newgeordent künstlich Lautenbuch

02. Ein newgeordent künstlich Lautenbuch

03. Ein newgeordent künstlich Lautenbuch

04. Ein newgeordent künstlich Lautenbuch

05. Ein newgeordent künstlich Lautenbuch

06. Ein newgeordent künstlich Lautenbuch

07. Ein newgeordent künstlich Lautenbuch

08. Ein newgeordent künstlich Lautenbuch

09. Ein newgeordent künstlich Lautenbuch

10. Ein newgeordent künstlich Lautenbuch

11. Ein newgeordent künstlich Lautenbuch

12. Ein newgeordent künstlich Lautenbuch

13. Ein newgeordent künstlich Lautenbuch

14. Ein newgeordent künstlich Lautenbuch

15. Ein newgeordent künstlich Lautenbuch

16. Ein newgeordent künstlich Lautenbuch

17. Ein newgeordent künstlich Lautenbuch

18. Ein newgeordent künstlich Lautenbuch

19. Ein newgeordent künstlich Lautenbuch

Hans Neusidler is unquestionably a major figure in the lute music of the Renaissance; he published eight books between 1536 and 1562 containing hundreds of dances, preludes, and intabulations obviously well used in their time, judging from the relatively high incidence of surviving copies of these editions. He sired 17 children, of whom Melchior Neusidler likewise became a famous lutenist, otherwise we don’t know a great deal about Hans Neusidler. While more than 50 of his compositions have been recorded within collections of Renaissance instrumental music, Passacaille’s Hans Neusidler: Ein newgeordinet Künstlich Lautenbuch featuring lutenist Bart Roose appears to be the first CD ever devoted solely to this composer.

Roose utilizes as his point of departure Neusidler’s first print, Ein newgeordinet Künstlich Lautenbuch (A Newly Ordered, Artistic Method for the Lute), which appeared in two volumes at Nuremburg in 1536. The first volume consists of 73 dances and preludes, and the second 47 intabulations, transcriptions of popular vocal pieces that were part of the bread and butter of every Renaissance lutenist. In the past, Neusidler’s dances have proven the main attraction to players, but this disc splits its 19 tracks between the two volumes. The intabulations from the second volume — as they tend to be longer and more ornate — come to the fore in terms of time elapsed, if not in number. Neusidler’s projection of Jacob Obrecht’s “Andernacken up dem Rhin” stands out as a particularly beautiful example of his work in the genre. Roose plays a six-course instrument built by Peter van Wonterghem after a Hans Frei lute in the Vienna Kunsthistoriches Museum dating from 1530. It has a pearly and warm tone, and Roose plays it with great care and sensitivity. In a way this is a little of a drawback; the program as a whole is rather low key and sometimes it’s difficult to keep track of where you are, though when a dance comes along it catches your attention. Something about Neusidler’s dances makes them sound different and distinctive from other pieces of their kind, whereas the intabulated pieces, in some cases, seem comparatively regular. There are choices of tempo, too, that one might question, such as in Lamora, Neusidler’s transcription of Heinrich Isaac’s familiar piece “La morra,” which seems, in Roose’s hands, impractically slow, under-accented, and awkward.

Despite these minor, debatable points about interpretation, Passacaille’s Hans Neusidler: Ein newgeordinet Künstlich Lautenbuch is a fine recital and likewise relaxing to listen to; the extraordinary qualities of both this album and its content indicate that an all-Neusidler recital on disc is probably something that is long overdue.