Composer: Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, Johann Sebastian Bach, Christophe Graupner, Johann Kaspar Fischer, Johann Kuhnau, Johann Balthasar Kehl

Performer: Anne Marie Dragosits

Format: FLAC (tracks)

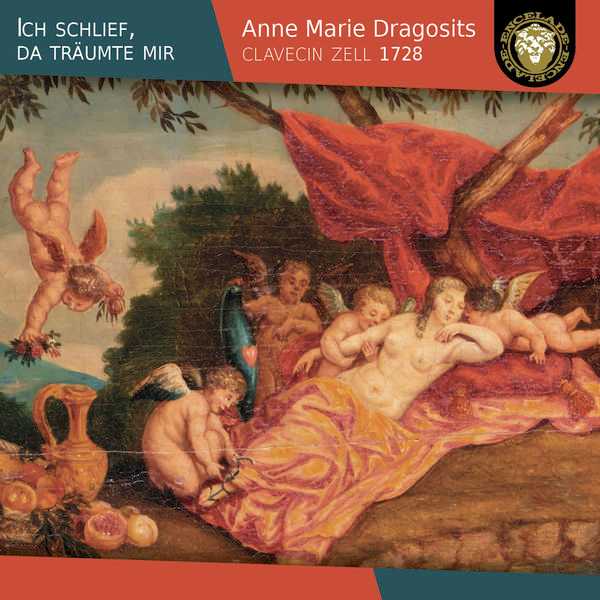

Label: L’Encelade

Release: 2021

Size: 1.35 GB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: yes

01. Bach CPE: La Stahl, Grave

02. Bach CPE: An den Schlaf

03. Bach CPE: La mémoire raisonnée

04. Bach WF: Réveille

05. Graupner: Febrarius

06. Fischer: Uranie

07. Fischer: Uranie

08. Fischer: Uranie

09. Bach JS: Praeludium (Harpeggiando)

10. Bach JS: Komm süßer Tod

11. Kuhnau: Suonata quarta, Hiskia agonizzante e risanato

12. Kehl: Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern

13. Bach CPE: Variations sur « Ich schlief, da träumte mir

14. Bach WF: Fantasia

15. Graupner: Partita VII. Partien auf das Clavier

For thousands of years, mankind has been concerned with the interpretation of dreams, seeking medical and philosophical explanations of all that happens to us during sleep. At the same time, mankind has been obsessed with the images of dreams – be they beautiful or terrible, like an imaginary theatre – offering a rich playground for all branches of art.

Hypnos, son of night and darkness, is the god of sleep. As Ovid reports, his sons are the Oneiroi, the dream gods being, Morpheus who is able to take on human form, Phobetor, the horror who slips into the skin of wild animals and Phantasos who appears in the form of inanimate nature. Hypnos’ realm is guarded by Hesychia (calm), Aergia (indolence) and Lethe (oblivion). While Hypnos is often called the “generous one,” his twin brother is Thanatos, “the gentle death”; and often the two often appear together.

These and other nocturnal visitors find their matching counterparts in music. The selection of musical pieces for this most subjectively arranged recording is as varied as night’s images. Certain titles make references to the night and dream worlds. Other works were chosen partly for describable musical reasons, partly in free association with my own subjective dream visions.

A significant stake in the choice of program was claimed by the highly characteristic sound of the harpsichord by Christian Zell (1728). As one of the few surviving and playable large German harpsichords, its clarity and transparency embodies the music of the German high baroque ideally. But the great sonic difference between the warm, resonant lower manual and a very brilliant and nasal upper manual (which is nevertheless equipped with great lyrical qualities) also provides the instrument – together with its charming lute stop and a four-foot stop that is as clear as a bell, along with the roaring sonority of the coupled registers – all the colours and possibilities necessary for gallant music. (Anne Marie Dragosits)

The extraordinary recital “Le clavecin mythologique”, also for the Versailles-based label L’Encelade, provides an original pretext for a colourful and inspired exploration of the harpsichord repertoire of eighteenth-century France (mainly). Once again, the Austrian Anne Marie Dragosits lavishes us with her art for enchantment and takes us into the heart of the night, a moment conducive to dreaming and beyond that, into her imagination and world of artistic creation. Taking its origins from the idea of sleep, which came from French music (and brought to its peak by Lully in his lyrical tragedies, starting with Atys), Dragosits invites us on a journey which takes – curiously, and this is where all the interest lies – its roots in Germany between the 17th and 18th centuries and not France.

The Bach dynasty is well represented on this album, from the sons to the father: Wilhelm Friedemann and his incredible Fantasia, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach and his Variations on “Ich schlief, da träumte mir” that preceed a few other pieces at the opening of the programme, including the very beautiful La Mémoire Raisonnée from a set of little-known miniatures, Wq. 117. From Johann Sebastian, Anne Marie Dragosits chose the too rare Praeludium (Harpeggiando), BWV 921, a true keyboard improvisation that is full of contrasts and explosive joy, whose hybrid tone recalls Buxtehude’s “stylus phantasticus”. The harpsichordist then inserts, here and there, according to her own whim – and no doubt her dreams – a few pieces by Graupner, Fischer and Kuhnau. From the former, two very beautiful pieces entitled “Sommeille”, taken from two different suites by the composer. On the sublime Christian Zell harpsichord of 1728 – one of the most beautiful harpsichords in the world, preserved in the Museum of Decorative Arts in Hamburg – Dragosits then deploys treasures of tenderness, as well as implacable majesty. Her playing is constantly impressive, even in the Passacaglia by Johann Caspar Ferdinand Fischer, the apotheosis of the first part of the programme, bursting with Lully like influences which were to have a strong influence on the young J. S. Bach.

A supreme testimony to a discreet harpsichordist with a captivating musicality, this recital “Ich schlief, da träumte mir”, has a highly original programme and often very subtle transitions. Bach’s Komm süßer Tod followed by Kuhnau’s Biblical Sonata No. 4 should not be enjoyed in any other way than on a stroll, especially as the instrument itself remains perpetually enchanting, with its incredibly deep bass and its stunningly beautiful lute playing; however if all this frightens you, perhaps start with the Sommeille from Graupner’s “Febrarius” Suite: such a moment of capricious gentleness and sublime tenderness will undoubtedly not leave you by the side of the road!