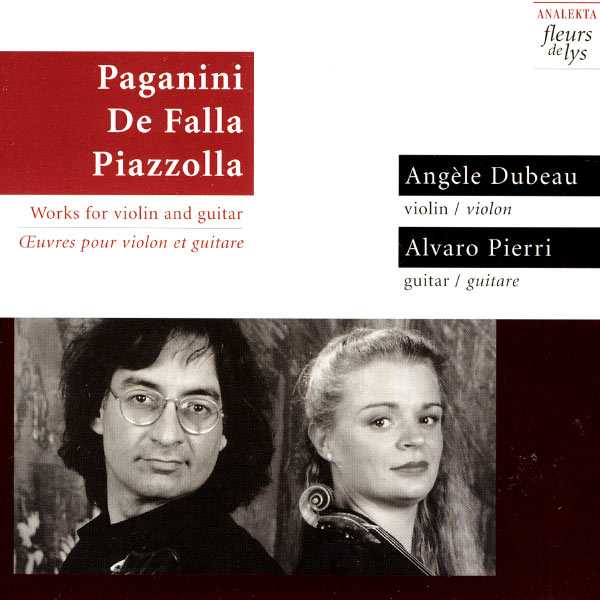

Composer: Manuel de Falla, Astor Piazzólla, Niccolò Paganini

Performer: Angèle Dubeau, Alvaro Pierri

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: Analekta

Catalogue: FL23034

Release: 1995

Size: 218 MB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: cover

Paganini: Sonata Concertata In A Major

01. I. Allegro Spiritoso

02. II. Adagio Assai Espressivo

03. III. Rondeau

04. Paganini: Cantabile For Violin And Guitar

Paganini: Cantone Di Sonate, Op. 64, No. 1

05. I. Introduzione Allegro Maestoso

06. II. Rondoncino

Falla: Canciones Populares Espanolas For Violin And Guitar

07. El Pano Moruno

08. Nana

09. Cancion

10. Jota

11. Asturiana

12. Polo

Piazzólla: Histoire Du Tango

13. Bordel 1900

14. Café 1930

15. Nightclub 1960

16. Concert D’Aujourd’hui

Paganini Sonata Concertata in A Major

Besides Franz Liszt, no virtuoso artist ever succeeded so well in capturing the public fancy as violinist Niccolo Paganini, born in Genoa in 1782, and who died in Nice (France) in 1840. Everywhere he went, his stunning violin pyrotechnics brought awe as well as tremendous applause, so much so that certain people even ventured to think that such incredible feats were the result of an alliance with the devil!

And there was some ground for it, too! A haughty attitude, a whitish face framed by jet-black hair and highlighted by overlong evening wear, as well as practice and composing shrouded in utmost secrecy called evidently for gossip and speculation: these were the times of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the devilry in the Tales of Hoffmann, Gœthe’s Faust, and the pervading ghosts in ballet and opera, such as Giselle and Robert-Le-Diable. Since his early youth, his father, a mandolinist, had sternly taught him the violin’s finer points. What is lesser known is that, through his father’s alternate teaching, and because of his liaison with a Tuscan lady of title between 1801 and 1804, when he had even given up the violin for the guitar, Niccolo also became a virtuoso on the guitar, or so claimed his contemporaries.

Therefore many of his works were written for a combination of violin and guitar, such as the three we have here. The Sonata Concertata is one of his few works where virtuosity is not only restricted to the violin: in its two happy flanking movements, and the enclosed, charming Adagio assai expressivo, the difficulty is fairly shared between the partners. Cantabile for Violin and Guitar The lovely Cantabile is one of the most beautiful pieces he ever wrote. Some of this music may well strike the listener as trivial, but it is seldom less than elegant.

Centone Di Sonate, Op. 64, No. 1

In the former work, Paganini the virtuoso was ever present. Here, we find the charmer, the charismatic performer idolized by women and envied by men every time he appeared on stage or in elegant drawing-rooms. So, having hardly anything to do to win public acclaim, he sometimes dwelt in the composition of lighter, more delicate and tender works such as this Centone, the first of a series of eighteen, strongly reminiscent of Rossinian and Verdian melodies. Lighter, by all means; but absolutely without critical connotation.

The three movements (Introduzione – Allegro mí¦stoso – Rondoncino) do show some virtuosity, naturally, but this time only for expressive purposes. De Falla Spanish Popular Songs (from a violin and guitar transcription by Kochansky and a voice and guitar transcription by Miguel Llobet) La Vida Breve (A Short Life) is one of Falla’s most important works: it wins him the first prize in the contest organized by the Royal Academy in 1905, and in writing it, allows him to live inforgettable experiences, thus marking his artistic life forever: The discovery and extensive use of spanish gypsy flamenco traditions and lore, which he saw performed every night in the “cafes-cantantes” of his youth for one, and the attendance, year after year of Zarzuela (Spanish operetta) performances prompt him to write for the voice, but in a manner in total accordance with the urge to create a national trend for music deeply rooted in Spain’s colorful musical past. The overwhelming success of Vida allows Falla to pause and reflect, to acknowledge former influences from Puccini and Wagner and to organize his musical world in, finally, a coherent whole.

It is in this perspective that we have to view and hear those seven songs, in his mind for many years. In later years, he will clearly state his position: “As for me, I think that, in popular song, spirit is more important than words: actually, rythm, melodic intervals and tone are the shaping agents of its flow, as well as its cadenzas. The people it stems from are living proof of it, as they are able to produce infinite variations on the purely melodic lines of those songs embedded in their collective conscience.”

These seven songs represent a tremendous achievement in this respect: Falla, within the consummate skill of perfect musical writing, incorporates an extraordinary rich and diversified folk material and creates a truly national expression. One might almost say like a musical tralelogue of domestic Spain, felt rather than heard through its purest songs and dances.

El pano moruno : This song is based on a celebrated ancient folksong from the Murcia region, with strong overtones of moorish rythms and melodies, and based on what is called “the andalucian cadenza,” A minor, G seventh, F and E major.

Nana : A cradle song, so ancient and popular that musicologists and common people alike refer to it as the Reverend Mother of folksong. Cancion: A high-caliber exercise in rythm, constantly opposing the vocal line to the pianistic accompaniment, one hand at a time. The result is fascinating.

Jota : A strong and invigorating peasant dance from Aragon, in norther Spain, but so popular that near-by provinces have their own version of it, in rythm as well as in spirit. Asturiana: This beautiful and austere melody stems directly from its celtic origins, not only with its clear-cut cadenzas, but also in the faint echœs of the Gaita, the spanish bagpipe.

Polo : Now is pure and authentic flamenco time. However, the Polo comes in two formats, as it were: the first is a fast 3/4 dance, a good example of which is the opening of Bizet’s fourth act in his opera Carmen, suggested to him by Manuel Garcia; the second is one of the mother songs of Cante Jondo (Deep Song), from which stems Soleares, Alegrias and Bulerias. Falla’s Polo keeps the obsessive note repetition and the wounded cry “Ayy” so closely connected with flamenco singing.

Piazzolla History of the Tango

Astor Piazzola, born in Argentina, and who died recently, can be considered as being instrumental in the revival of the tango form and spirit. Born about a hundred years ago in the prostitution houses of Buenos-Aires’s harbour, the tango was first danced by men only, to dissipate boredom and long wait… These men, immigrants, lost, looking for imaginary gold and prosperous life, in this newly-born Argentina, and hoping against all hopes for a girl who would give them back their lost paradise… Sweat, tears, jealousy, death and blood were also mixed in the tango cauldron. And its stringent vitality made a hit in the popular café-concert of Europe until Rudolph Valentino, in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (Rex Ingram, 1921) propelled himself to immortal fame by dancing one of the hottest tangos on record. And so went the tango, year after year, slowly becoming a lovely but common ballroom dance, performed everywhere and by everybody.

Then came Piazzola and everything changed. His talent and background suffused the very heart of the tango with new and pulsating latin blood, rediscovering at the same time the very soul of the people who created it through sweat and tear. Doing so, he succeeded, not only in creating a brand new mean of expression, but also made Argentina aware of its roots and traditions, as much as flamenco expresses the very core of Gypsy soul and way of life.

The History of the Tango is a particularly relevant piece to carry out the Piazzolla genius. It is in four parts, each depicting a particular moment in the evolution of the dance:

Bordel 1900 reverts to the original wheedling tango. The men. Heavy and dense smoke. Air sticky and moist. In the back, the bandoneon wails, bringing temporary relief and oblivion in weary eyes, as time slowly dissolves in the music…

Café 1930 : Now the girls are here, weaving their pitiful webs of deceit and false love, or letting out anguished cries of betrayed desire. And the tango whirls around itself, sending hearts and lives in a deadly vortex of passion, lust and deception. Rather than dance the tango, people now listen to it.

Nightclub 1960 : Beautifully appointed “salons,” plush trimmings, mirrors and champagne cannot hide successfully the deadly traps and the cruel games played by a corrupt and decadent society, dominated by money, political power and violence, sending its members in even deeper vortexes.

Concert d’aujourd’hui : At last, the tango has played all its cards, trumps and aces. Now is the time for a new dawn, as Piazzolla boldly gœs where no man has gone before: the new blood is provided by the great classical masters of the twentieth century: Bartok, Stravinsky, Ginastera, Ravel and many others who, under the skilled hands of Piazzolla, become the everflowing fountain of inspiration for a wonderful new tango, both sung and danced, now part of the international musical heritage and directly headed for the future.