Composer: Ludwig van Beethoven, Franz Peter Schubert

Performer: Artur Schnabel

Orchestra: Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: Frederick Stock

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: RCA

Catalogue: 88985389712

Release: 2017

Size: 417 MB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: cover

CD 01

Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 4 in G major, Op. 58

01. I. Allegro moderato

02. II. Andante con moto

03. III. Rondo – Vivace

Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat major, Op. 73 ‘Emperor’

04. I. Allegro

05. II. Adagio un poco mosso

06. III. Rondo – Allegro

CD 02

Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 30 in E major, Op. 109

01. I. Vivace non troppo

02. II. Prestissimo

03. III. Gesangvoll, mit innigster Empfindung (Variations 1-6)

Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 32 in C minor, Op. 111

04. I. Maestoso – Allegro con brio ed appassionato

05. II. Arietta – Adagio molto semplice cantabile

Schubert: 4 Impromptus, D899 (Op. 90)

06. Impromptu No. 1 in C Minor

07. Impromptu No. 2 in E-Flat Major

08. Impromptu No. 3 in G-Flat Major

09. Impromptu No. 4 in A-Flat Major

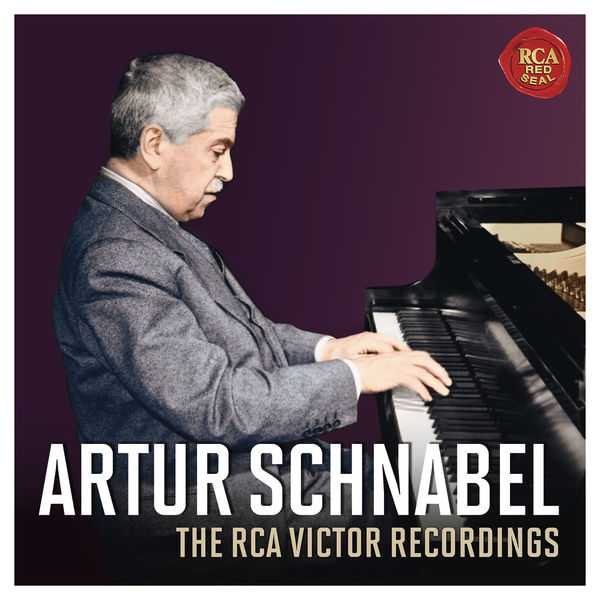

Sony Classical pays tribute to Artur Schnabel – one of the 20th century’s most influential pianists and musical thinkers – with a 2-CD set of his complete American RCA Victor recordings.

Artur Schnabel – The RCA Victor Recordings brings together all of the pianist’s sessions for RCA Victor, recorded within an intense two months of activity in 1942. Beethoven’s G major and “Emperor” Concertos with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (conducted by its long time music director Frederick Stock) first appeared on 78s. Two late Beethoven Sonatas, No. 30 in E major op. 109 and No. 32 in C minor op. 111 were issued for the first time in 1976, inviting comparisons alongside Schnabel’s much imitated early 1930s versions. Also from the 1942 sessions are the previously unpublished Schubert Impromptus D 899, a significant addition to Schnabel’s discography.

Born in 1882 and raised in Vienna, Artur Schnabel began lessons at nine years old with Theodor Leschetitzky. The legendary pedagogue recognized his young pupil’s unusual nature, and steered him towards Schubert’s then-neglected sonatas, saying, “You will never be a pianist, you are a musician.” After his 1898 Berlin debut, Schnabel began touring as a soloist, as a chamber player, and in a lieder duo with his future wife, contralto Therese Behr.

Although Schnabel commanded a wide repertoire, he was best known as an interpreter of the Austro-German classics of Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert, with forays into Schumann and Brahms – as he put it, “music which I consider better than it can be performed.”

From 1925 Schnabel taught at the Berlin State Academy until leaving the city in 1933 after the Nazi Party took control. He became the first pianist in history to record all 32 Beethoven Sonatas, and taught master classes at Tremezzo, Lake Como before moving to the United States in 1939, where he became a naturalized citizen five years later. He returned to Europe after the war, and died in 1951 at Lake Como.

Artur Schnabel (1882–1951) is widely regarded as one of the best pianists of the 20th century. Renowned for his intellectual rigor, profound musicality, and distinctive interpretative style, Schnabel made an indelible mark on the world of classical music. His legacy, not just as a performer but also as a teacher and composer, continues to influence pianists today. This essay explores Schnabel’s life, career, artistic philosophy, and lasting impact on the music world.

Early Life and Training

Artur Schnabel was born in the then Austro-Hungarian Empire, in the city of Lipnik, near Vienna (now part of Poland), into a family of Jewish descent. His musical talent was evident from a young age, and he began studying the piano with his mother before attending the Vienna Conservatory at the age of 15. Schnabel’s early teachers included the renowned pedagogues Richard Robert and Josef Dachs, both of whom helped hone his technical and musical skills.Schnabel’s academic and musical education was rooted in the traditions of European conservatories, and his immersion in the music of composers such as Beethoven, Brahms, and Schubert would lay the foundation for his lifelong fascination with the great Classical and Romantic repertoire. His early training focused not just on technical proficiency but also on cultivating a deep understanding of musical structure and interpretation.

A Virtuoso in Performance

Schnabel’s early career as a performer was marked by rapid success. He made his debut at the age of 18 in Vienna, and soon thereafter began performing across Europe. His reputation as a virtuoso grew steadily, and by the early 20th century, he was an established figure on the concert circuit. However, Schnabel was never interested in merely being a “showman” or dazzler at the piano; he was an artist driven by the desire to reveal the full depth of the music he performed.His technical prowess was undeniable, but Schnabel’s true gift lay in his intellectual and emotional engagement with the music. He was especially admired for his readings of Beethoven’s piano sonatas and concertos, which were marked by a depth of insight and a balance between virtuosity and a profound understanding of the composer’s intentions. Schnabel’s interpretations of Beethoven have been described as monumental and transformative, shaping how future generations of pianists would approach this challenging repertoire.

The Beethoven Legacy

Beethoven’s music, especially his piano works, played a central role in Schnabel’s career. His interpretation of Beethoven’s piano sonatas was groundbreaking. Where many pianists of the time leaned toward a more flamboyant or emotionally unrestrained approach, Schnabel embraced Beethoven’s music with a clarity and intellectual precision that reflected his keen understanding of the composer’s innovations.His 1930s recordings of Beethoven’s 32 piano sonatas, made for the German record label Polydor, are considered among the most important and influential recordings of the 20th century. Schnabel’s interpretations of Beethoven were notable not just for their technical brilliance but also for their structural clarity, where he sought to illuminate the architecture of each piece. His readings of the sonatas are often described as uncompromising, emphasizing the music’s complexity and depth, rather than indulging in surface-level sentimentality.

Schnabel’s approach to Beethoven was not just about technical prowess; it was about understanding the very soul of the music. In his performances, he gave voice to Beethoven’s inner turmoil, joy, struggle, and transcendence. This intellectual and emotional engagement with the music made Schnabel’s Beethoven interpretations so compelling and still serves as a model for pianists today.

Intellectual and Artistic Philosophy

Schnabel’s musical philosophy was deeply intellectual. He was a thinker as much as a performer, and he often talked about music in philosophical terms. For him, interpretation was not just a matter of personal expression but a search for the true meaning of a work. Schnabel believed that understanding the music’s structure and form was essential to delivering a truly meaningful performance. His approach to piano playing, while technically demanding, was also analytical—he was determined to get beneath the surface of the music.Schnabel was also critical of the tendency among some performers to prioritize technical brilliance over musical expression. He felt that many pianists of his time were more concerned with showing off their technical prowess than with conveying the depth of the music. In his view, technical skill was essential, but it should always serve the music, not the performer’s ego.

In addition to his work as a performer, Schnabel was a highly respected teacher, influencing several generations of pianists. His pupils included some of the leading pianists of the 20th century, such as Leon Fleisher, Mieczysław Horszowski, and Alfred Brendel. As a teacher, Schnabel was known for his intellectual rigor, encouraging his students to think deeply about the music they played and to approach every piece with the same combination of technical mastery and intellectual engagement that he brought to his own performances.

Composer and Musical Pedagogue

In addition to his career as a performer, Schnabel was also a composer, although his output in this field was relatively modest. His compositions included piano works, chamber music, and orchestral pieces, but none of them achieved the level of fame or recognition that his interpretations of Beethoven did. Nonetheless, his compositions reflect the same intellectual depth and careful craftsmanship that characterized his approach to performance.As a teacher, Schnabel was equally dedicated to his students. He believed that the piano could be a tool for the deep exploration of music, and he emphasized the importance of understanding both the technical and conceptual aspects of music. Schnabel’s teaching was marked by an insistence on intellectual engagement with music, urging his students to consider the underlying structure and meaning of each piece. His approach to teaching was thus aligned with his own artistic philosophy: music was not just to be performed but to be understood and interpreted with the utmost care and respect.

Recordings and Legacy

Schnabel’s legacy is most strongly felt through his recordings, which remain benchmarks of piano playing. His early recordings, particularly of Beethoven’s works, continue to be cherished by musicians and listeners alike for their technical brilliance and interpretative depth. Despite the limitations of recording technology in the early 20th century, Schnabel’s recordings capture the essence of his pianism—clear, structured, and intellectually rigorous, yet full of emotional intensity.In the decades following his death, Schnabel’s contributions to the piano world were celebrated through the continued reverence for his recordings and the teachings of his students. His influence can be heard in the playing of many pianists who came after him, particularly those who sought to combine technical precision with emotional depth.

Schnabel’s significance also lies in his ability to bridge the gap between the 19th and 20th centuries. While he was a master of the Romantic repertoire, he was also open to the modern music of his time. He performed and recorded works by composers such as Schoenberg and Stravinsky, demonstrating his openness to the musical innovations of the 20th century. This ability to balance the old and the new further solidified his position as one of the greatest musicians of his era.

Artur Schnabel remains a towering figure in the history of classical music, admired for his depth of understanding, technical mastery, and interpretive insight. His interpretations of Beethoven’s piano sonatas and concertos continue to shape the way pianists approach this repertoire, and his pedagogical legacy has influenced countless students who have gone on to become leading musicians in their own right. Schnabel’s legacy is a testament to the power of intellectual engagement with music, proving that great piano playing is not just about technical virtuosity, but about the ability to communicate the deep emotional and structural truths of a composition. As both a performer and a teacher, Schnabel’s impact on the classical music world remains profound and enduring.