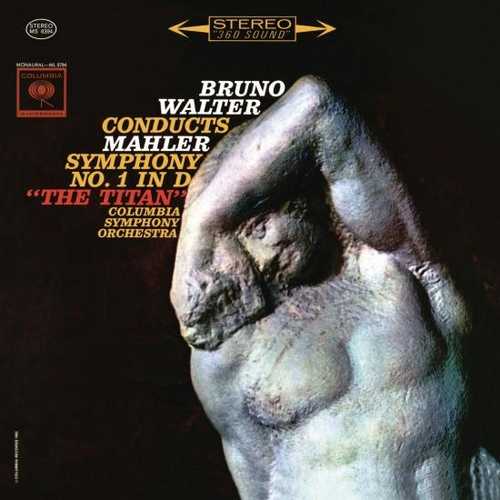

Composer: Gustav Mahler

Orchestra: Columbia Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: Bruno Walter

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: Columbia

Release: 2019

Size: 2.16 GB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: cover

Symphony No. 1 in D Major “Titan”

01. I. Langsam. Schleppend. Wie ein Naturlaut. Im anfang sehr gemächlich

02. II. Kräftig bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell

03. III. Feierlich und gemessen, ohne zu schleppen

04. IV. Stürmisch bewegt – Energisch

For many years Bruno Walter was a friend and collaborator of Gustav Mahler, and his interpretations of the composer’s symphonies are generally considered unsurpassed models. The „official“ studio recordings of Mahler’s works, however, were made towards the end of his life and perhaps do not give a good enough idea of the Bacchic frenzy that characterised the German conductor’s early interpretations of them. In this beautiful 1939 live recording, instead, the Bacchic frenzy is all there, fascinating from the first measures and reaching an apex in the powerful and impressive Finale.

“To write a symphony means, to me, to construct a world with all the tools of the available technique,” wrote Gustav Mahler. The World in a Symphony-the experiences, qualities and meaning of life enfolded in tone. Mahler, the most ardent of the Romantics in his belief in the bond between human existence and music, spent his career pursuing this lofty aim. He once said, “My whole life is contained in them [i.e., the first two symphonies]: I have set down in them my experience and my suffering….To anyone who knows how to listen, my whole life will become clear, for my creative works and my existence are so closely interwoven that, if my life flowed as peacefully as a stream through a meadow, I believe I would no longer be able to compose anything.” Mahler certainly had a full share of rocks and rapids in the stream of his life: deaths of loved ones, including a child, only weeks apart; a critical heart condition that precipitated his premature death at the age of 50; severe bouts of depression that led him to seek the counsel of Sigmund Freud; and great difficulties in finding acceptance for his works. Though those experiences were still in the future when he wrote this First Symphony, Mahler nevertheless embodied profound thoughts and emotions in this early work. Written during his tenure as conducting assistant to the great Arthur Nikisch at Leipzig, the D major Symphony reflects Mahler’s concerns with romantic love, with establishing himself as a creative artist, and with finding a musical language proper to express his inner turmoil.

Though he did not marry until 1902, Mahler had a healthy interest in the opposite sex, and at least three love affairs touch upon the First Symphony. In 1880, he conceived a short-lived but ferocious passion for Josephine Poisl, the daughter of the postmaster in his boyhood home of Iglau, and she inspired from him three songs and a cantata after Grimm (Das klagende Lied “The Song of Lamentation”) that contributed thematic fragments to the Symphony. The second affair, which came early in 1884, was the spark that actually ignited the composition of the work. Johanne Richter possessed a numbing musical mediocrity alleviated by a pretty face, and it was because of an infatuation with that singer at the Cassel Opera, where Mahler was then conducting, that not only the First Symphony but also the Songs of the Wayfarer sprang to life. The third liaison, in 1887, came as the Symphony was nearing completion. Mahler revived and reworked an opera by Carl Maria von Weber called Die drei Pintos (“The Three Pintos,” two being impostors of the title character), and was aided in the venture by the grandson of that composer, also named Carl. During the almost daily contact with the Weber family necessitated by the preparation of the work, Mahler fell in love with Carl’s wife, Marion. Mahler was serious enough to propose that he and Marion run away together, but at the last minute she had a sudden change of heart and left Mahler standing, quite literally, at the train station. The emotional turbulence of all these encounters found its way into the First Symphony, especially the finale, but, looking back in 1896, Mahler put these experiences into a better perspective. “The Symphony,” he wrote, “begins where the love affair [with Johanne Richter] ends; it is based on the affair that preceded the Symphony in the emotional life of the composer. But the extrinsic experience became the occasion, not the message of the work.”