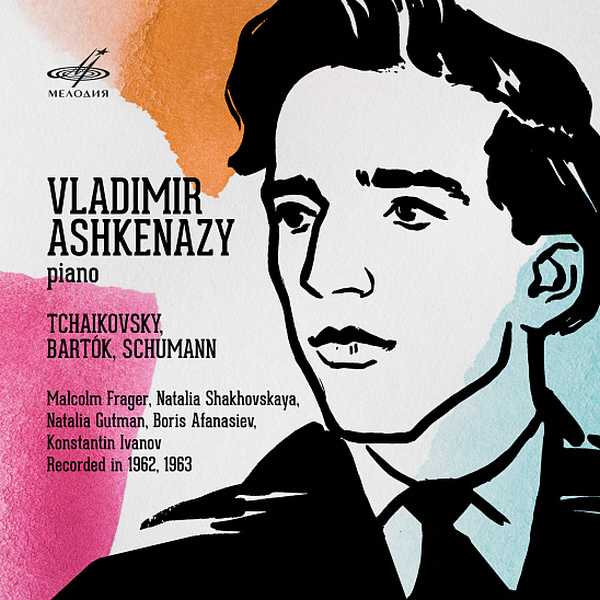

Composer: Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky, Béla Bartók, Robert Schumann

Performer: Vladimir Ashkenazy, Malcolm Frager, Natalia Shakhovskaya, Natalia Gutman, Boris Afanasiev, Ruslan Nikulin, Valentin Snegirev

Orchestra: USSR State Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: Konstantin Ivanov

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: Melodiya

Catalogue: MEL CO 0412

Release: 2020

Size: 364 MB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: yes

Tchaikovsky: Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-Flat Minor, Op. 23:

01. I. Andante non troppo e molto maestoso

02. II. Andantino semplice

03. III. Allegro con fuoco

Bartók: Tchaikovsky: Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion, Sz. 110

04. I. Assai lento – Allegro troppo

05. II. Lento, ma non troppo

06. III. Allegro non troppo

07. Schumann: Andante and Variations in B-Flat Major for Two Pianos, Two Cellos and Horn, WoO 10

“Vladimir Ashkenazy is an outstanding pianist… What a temperament, what awill! He imperiously takes possession of the music he performs… He is twenty-five years old and the future that lies before him is beautiful”. This is how Henryk Sztompka, a member of the piano jury and vice-president of the Chopin Society in Warsaw, praised the winner of the II International Tchaikovsky Competition in 1962. Fifty-eight years later, in January 2020, Vladimir Ashkenazy, a pianist, conductor, and winner of seven Grammy Awards, announced the complete cessation of his performing and concert activities.

Vladimir Ashkenazy’s worldwide fame reached its peak after he fled to the West. But his career skyrocketed in the late 1950s and early 1960s, when a series of victories at international competitions made the recent graduate of the Moscow Conservatory one of the leading musicians of the former USSR.

He was born in the family of the famous variety pianist and accompanist David Ashkenazy. The future artist’s childhood fell on the tough 1940s, but his parents directed all their efforts to make sure that their son’s outstanding musical abilities were properly developed. At the Central Music School of the Moscow Conservatory, he was taught by Anaida Sumbatian. She, who brought up more than one generation of musicians, instilled a strict taste, a sense of the style of the music they played, and utmost self-discipline in her students. At the conservatory, Ashkenazy studied with Lev Oborin, a legendary winner of the First International Chopin Competition (however, his assistant Boris Zemlyansky, an outstanding teacher whose destiny was so dramatic, was the one thanks to whom “I can say that music is my life” according to Ashkenazy and who devoted more attention to the students).

In 1955, Vladimir Ashkenazy played his first recital at the Grand Hall of the Conservatory. A year later, he was awarded the silver medal of the Chopin Competition in Warsaw and the Grand Prix of the Queen Elisabeth Competition in Brussels. That brilliant victory was the beginning of the worldwide recognition – his first tour in West Germany and the USA took place shortly after that. As the pianist later admitted, he had to compete at the International Tchaikovsky Competition against his will. He voluntarily refused to participate in it in 1958, but now the young musician had to seriously think about his career (according to a private eye, his “suspicious” behavior during the American tour threatened to make him a person who would not be allowed to travel abroad). In addition, the pressure from above intensified – after Van Cliburn’s unexpected victory at the first competition, the presence of a Soviet candidate who would confidently seek the first prize was a matter of paramount importance to the authorities. And Vladimir Ashkenazy managed to live up to expectations.

He was a confident leader of the competition marathon in the first two rounds – with rare exceptions, the jury unanimously gave him the highest points. “Everything in his performance … was thought out and polished to the smallest detail,” critic Konstantin Adjemov wrote on the pages of Soviet Music magazine. “… Every note is alive under his fingers, every sound is enjoyed by the artist, not loudly, but somehow surprisingly chastely, and every sound we hear becomes the property of the audience”.

“His victory is undeniable,” the above-mentioned Henryk Sztompka stated. However, the selfcritical pianist did not think highly of his performance of the Tchaikovsky concerto in the final round and gave credit to Britain’s John Ogdon, who shared the first prize with him. A year later, he recorded the same concerto in London with the London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Lorin Maazel and never returned to it again.

The recording released shortly after the competition (with the USSR State Symphony Orchestra conducted by Konstantin Ivanov) is actually not inferior to the London one. Even more polished, restrained in some details, and with a slightly more defined relief of the culmination take-offs, the 1963 recording captures the artist’s constant desire for excellence (more achievable in the calm environment of the Decca studios). On the other hand, the severity of competitive experiences with some inevitable losses is refracted into an increased emotional tone of performance, which is transmittable even through the audio tape. The theme of Andantino is “sung” with warmth and cordiality, the finale is breathtakingly swift, the emotion of the final passages of the extreme parts is powerful – the surviving audio document of 1962 undoubtedly captured not just “another competition victory”; what we have before us is a bright performing achievement, an important milestone on the artistic path of the outstanding artist.

At that time, Vladimir Ashkenazy was already married to the Icelandic pianist Þórunn Jóhannsdóttir who studied at the Moscow Conservatory. By the end of 1962, the couple firmly decided to leave for Great Britain. However, the Soviet authorities did not want to lose such a brilliant performer, who had conquered the public on both sides of the Atlantic by the age of 25. Ashkenazy was offered a unique option of the so-called “open visa”, with which he could retain a right to freely enter and depart from the USSR while remaining a Soviet citizen. In order to confirm his “loyalty,” Ashkenazy returned to Moscow for a short time in May 1963 and played a number of concerts (Melodiya released a phonogram of one of them in 2019) and made several studio recordings.

The Bartók and Schumann ensembles were recorded in collaboration with the talented American pianist Malcolm Frager. The latter, a researcher musician and connoisseur of the Russian language and culture, was one of the few who performed Tchaikovsky’s First Concerto in the original composer’s version. He met Ashkenazy during his first U.S. tour and stayed on friendly terms with him ever after. In 1960, Frager won the Queen Elisabeth Competition in Brussels, and three years later performed for the first time in Moscow (in 1964, the two pianists recorded Mozart’s Sonata KV448 in London).

Béla Bartók finished his Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion in 1937. It was commissioned by the Basel International Society for Contemporary Music and happened to be the Hungarian composer’s last piano work written in his homeland. In his earlier works, Bartók was inclined towards an “anti-romantic,” emphasized percussion interpretation of piano sonority; on the other hand, the composer persistently experimented with the timbres of the percussion group. The sonata synthesizes Bartók’s artistic search in both directions – he found a perfect balance between the sound of two pianos and an ensemble of seven instruments (timpani, bass drum and snare drum, cymbals, tomtom, triangle and xylophone). According to the composer’s idea, “now the percussion tint the timbre of the piano, then emphasize the most important accents, then intonate the motifs that are a counterpoint to the piano part; finally, the timpani and xylophone often perform themes of primary importance” (in the finale, these instruments actually perform a solo to the “accompaniment” of two pianos).

The early 1960s saw a surge of interest in Bartók’s music in the USSR. After a 25-year ban, his works were performed by domestic and foreign musicians at the concert halls of Moscow and Leningrad. The Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion was performed for the first time in this country by the piano duet of Sviatoslav Richter and Anatoly Vedernikov, while Maria Yudina and Viktor Derevyanko recorded their version (the young soloists of the USSR State Orchestra Viktor Snegirev and Ruslan Nikulin played the percussion in both cases; they are also featured on this recording).

An outstanding interpreter of Prokofiev’s and Shostakovich’s works, Vladimir Ashkenazy subsequently repeatedly turned to Bartók’s music. In its harsh sounds and “steel” rhythms, he revealed a complex spiritual world of one of the greatest music creators of the twentieth century.

Robert Schumann’s Andante and Variations written in 1843 was never published during the composer›s lifetime (the original was published by Johannes Brahms half a century later). The bright emotionality and freedom of musical expression make this piece similar to the piano cycles of the 1830s, distinguishing them from a number of Schumann’s more restrained and “classical” chamber opuses. The low popularity of Andante and Variations is associated with its uncommon line-up, possibly “improvised” at one of the musical recitals in the composer’s house (Schumann later arranged the piece for two pianos and published it as Op. 46). The piano parts are dominant, but their combination with two cellos and a French horn gives rise to some amazing timbres and challenges the performers to find the right sound balance.

This uncommon “quintet” is played by a truly stellar line-up. Ashkenazy and Frager are joined by the then recent winners of the Tchaikovsky Competition – cellists Natalia Shakhovskaya (first prize) and Natalia Gutman (third prize), who were beginning to rise to musical stardom, and Boris Afanasiev, a French horn virtuoso and winner of the international competitions in Moscow and Prague (at the time, he was a soloist of the Grand Symphony Orchestra of the All-Union Radio). It feels like the young musicians were happy to play together. That is why their version of this extraordinary confession of the 33‑year-old Schumann, a rebellious romanticist, who found the long-awaited shelter for his spirit and thought, sounds so natural and unforced.

Boris Mukosey