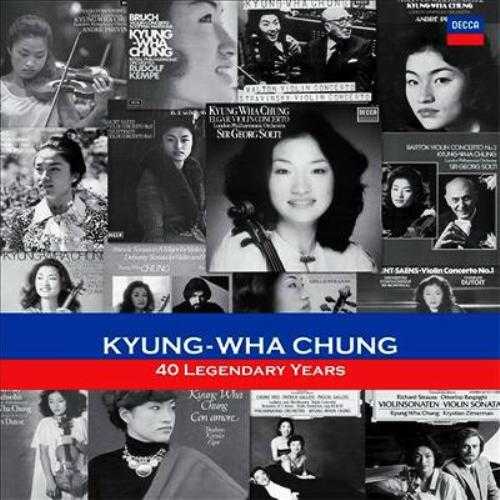

Performer: Akiko Suwanai

Orchestra: City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: Sakari Oramo

Composer: Jean Sibelius, William Walton

Audio CD

Number of Discs: 1

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: Decca

Size: 279 MB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: yes

01. Violin Concerto in D minor, Op. 47: 1. Allegro moderato

02. Violin Concerto in D minor, Op. 47: 2. Adagio di molto

03. Violin Concerto in D minor, Op. 47: 3. Allegro, ma non tanto

04. Violin Concerto: 1. Andante tranquillo

05. Violin Concerto: 2. Presto capriccioso alla napolitana – Trio (Canzonetta)

06. Violin Concerto: 3. Vivace

Suwanai, Sibelius, Walton: Violin Ctos: A surprising, gorgeous 20th century concerto coupling, Bravo

I finally got this disc in surround sound super audio. I have long been a fan of the Sibelius symphonies on Warner, with Oramo leading the Birmingham band. Sadly those were not widely released in USA except occasionally available as imports. I finally got them piecemeal from overseas. Then I noted that Oramo was leading Birmingham again, to accompany Akiko Suwanai in the violin concerto.

The companion piece struck me at first as less welcome. I have heard the Walton violin concerto repeatedly; and yet never quite got it all down. The Walton gets plays brilliantly in virtuoso readings. (Jascha Heifetz, Nigel Kennedy, Salvatore Accardo, James Ehnes, Maxim Vengerov) It sometimes gets played with a sort of modern soulfulness, like the updated renewal of romantic melody line we in USA tend to associate with those other contemporary violin concertos by Samuel Barber, Gian Carlo Menotti, William Schuman, David Diamond, Ned Rorem, William Bolcom. (Joshua Bell, Tasmin Little, Ida Haendel, Dong-Suk Kang)

My take on the Sibelius is just the opposite. I hear it, I totally get it, across a number of different readings. (My favs? Tossy Spivakovsky, Jascha Heifetz, Salvatore Accardo, Cho Liang Lin, Anne Sophie Mutter, Gil Shaham, Pekka Kuusisto, Gidon Kremer, Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg, Izthak Perlman with Leinsdorf, Eugene Fodor, Hu Kun with Menuhin, David Oistrakh with Ormandy, Boris Belkin with Ashkenazy or Hirokami, Maxim Vengerov, Henryk Szeryng – with special nods for the long lost PRT Label reading by Yuval Yaron and the Analekta reading by Angele Dubeau)

Let’s mention one more star? Suwanai plays a Strad, named The Dolphin (1714) on loan to her from the Nippon Foundation. No doubt, part of the stunning and deeply musical impact the violinist makes on this high resolution audio disc must be attributed to the near-mystical capabilities of the Stradivarius. Can we safely say, a Strad knows a worthy violinist when one comes along? Bravo.

If the violin is a star, then so, also, must the surround sound superaudio master on this recorded performance get star status. The engineers have done a beautiful job, and the home disc carries their full-frequency, warm, top-notch sound right into your home listening room. Bravo. Not only is the Strad caught well, so it the band (full, detailed), plus room touches to reinforce the tonal body (especially nice in Sibelius’ low strings, for example).

Another star aspect of this disc is its conductor, Sakari Oramo. He is from the wunderkind Finnish master classes taught at the Sibelius Academy by Jorma Panula. His complete symphony series of the Sibelius pretty much showed what he could do with the composer’s music; and he repeats or continues that high excellence as accompanist to Suwanai. So what does Oramo offer us, as a Sibelius conductor? Well. Lots, lots, lots. You pretty much have to go back to the early days of recordings, to figures like Robert Kajanus or Tauno Hannakainen, to hear the likes of Oramo. If one of our touchstone Sibelius conductors has been Paavo Berglund for several decades (and I do, indeed, like his Sibelius recordings very much, often); then Oramo equals or tops him. He brings out the structure strength, rock solid, of Sibelius orchestral music, takes flexible slow tempos which allow him to set fire to the musical details with a masterly grand sweep, and generally let’s Sibelius be all that Sibelius can be. There is a certain, ineffable devotion and discipleship that comes across when Oramo is leading Sibelius – like hearing Mahler or Bruckner or Brahms or Mozart from some leader who really believes in the music and in the composer; who has long steeped and stewed in the composer, internalizing a style and a sound world to amazing performance heights.

As the youngest ever winner of the 1990’s International Tchaikovsky violin competition, we might expect Suwanai to have big instrumental chops. But as the indicators, Strad plus conductor, show: She is pure L’Oreal – worth every bit of it.

From the first opening notes that she floats on the Sibelius above murmuring orchestra violins, right through her elegant Nordic Light Platinum misting of a very finely spun slow movement main melody (gone bardic and operatic and breathing vocal), to the galumphing galoshes big snow tread of the concluding movement – all is committed playing, indeed. As soloist, Suwanai manages to equal Oramo; and that is saying something, whether one hears the soloist against the conductor or vice versa, or whether one hears either soloist or leader, compared to some pretty stiff recorded competition. As musical partnerships go, Suwanai and Oramo lift right up there, floating around high up, with the likes of Lin and Salonen, Spivakovsky and Hannakainen, Bravo.

All amazed, we come to the prickly matter of doing the Walton violin concerto, next.

Now Walton immediately stakes out his romantic territory with an extended, long opening melody. Here, Suwanai is full-blooded yet exhibiting touches of restraint. She keeps that long, long paragraph of long, long melody from going all gooey-sticky in musical melt-down. So far, so good. It is not at all easy to balance Walton like she is doing. Oramo and the band in Birmingham pick right up on this tight-rope outing. Their follow up to the opening melody is balanced and integrated, too. As in the Sibelius, Oramo and Suwanai are tight together. Ditto, the band.

When Walton has the band break in with busier, jazzier noises, Suwanai manages the difficult transition from that long opening melody well sung, to the violin skittles the composer writes up for the soloist. Yet as all that quick-tempo plays out, she floats believably back to the long melodies, via sparkling trills and judiciously candle-lit rubato. Harp and woodwind touches, for once, do not sound cheap or glitzy in the contexts she has been setting as soloist, back up by conductor, back up by orchestra. When the full band departments flow in, emphasizing Walton’s pointed modernist song, they stay warm while also able to show off, virtuoso and brilliant. The Birmingham hall beautifully supports and cradles the constant balancing acts, warmth-song with virtuoso-precision. Is this a gift, to play those Walton melodies as song (complete with early-modern 20th century angles), never going sappy or mushy, never having the phrases fall apart into musical pieces?

All involved do get faster and play more improvisationally, for the second concerto movement. It is marked, cappriccioso, and further, all napolitana. Yet everybody can convincingly scale back, too, back to floating those long, angular Walton melodies which are so difficult to make sound too cool or too hot. Oramo and the band get the jazzy touches just right, too; even when they are interrupting those angular melodies. Hearing all that reminds me of an old music teacher who always asked me: Where are you playing from? Where are you playing to? What happens in between? For once the frequent gear shifts in this second movement do not at all fall apart, nor tempt one to prefer the slow over the fast, the fast over the slow, passages.

The last movement goes well. It marches smartly long, bringing off its canon-fugato lines, opening out fairly soon again into that typical Walton melody. The composer’s skipping intervals do not have the rock solid structural logic to express what intervals are telling us, say, in all four movements of the Stravinsky violin concerto. At least this reading conveys the forward movement and the purposeful pointing, so that a listener does not quite end up resenting the faster passages for interrupting the musing slow melody ones. Part of this magic is that Suwanai does not try to play past the angular turns in the line, nor round them off too smoothly; yet never lets those sharp angles break up the melody or line, either. This cannot be at all easy to carry off. Then think, I am going to double-stop those lines. Oh well. Bravo, bravo.