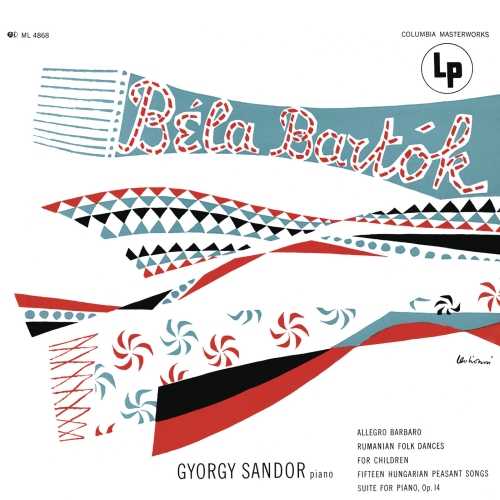

Composer: Béla Bartók

Performer: György Sándor

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: Columbia

Release: 1955/2020

Size: 406 MB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: cover

01. Allegro barbaro, Sz. 49

Romanian Folk Dances, Sz. 56:

02. 1. Stick Dance. Allegro moderato

03. 2. Belt Dance. Allegro

04. 3. The Stamper. Andante

05. 4. Dance from Bucium. Moderato

06. 5. Romanian Polka. Allegro

07. 6. Fast Dance. Allegro. Più allegro

For Children, Sz. 42 (1945): Vol. I:

08. 6. Study for the Left Hand. Allegro

09. 10. Children’s Dance. Allegro molto

10. 13. Ballad. Andante

11. 14. Allegretto

12. 15. Allegro moderato

13. 18. Soldier’s Song. Andante non troppo

14. 19. Allegretto

15. 21. Allegro robusto

For Children, Sz. 42 (1945): Vol. II:

16. 25. Parlando

17. 26. Moderato

18. 30. Jeering Song. Allegro ironico

19. 31. Andante tranquillo

20. 32. Andante

21. 33. Allegro non troppo

22. 34. Allegretto

23. 35. Con moto

24. 36. Drunkard’s Song. Vivace

25. 37. Swine-herd’s Song. Allegro

26. 39. Allegro moderato

27. 40. Swine-herd’s Dance. Allegro vivace

15 Hungarian Peasant Songs, Sz. 71:

28. 1. Four Old Tunes. Rubato

29. 2. Four Old Tunes. Andante

30. 3. Four Old Tunes. Poco rubato

31. 4. Four Old Tunes. Andante

32. 5. Scherzo. Allegro

33. 6. Ballad. Andante

34. 7. Old Dance Tunes. Allegro

35. 8. Old Dance Tunes. Allegretto

36. 9. Old Dance Tunes. Allegretto

37. 10. Old Dance Tunes. L’istesso

38. 11. Old Dance Tunes. Assai moderato

39. 12. Old Dance Tunes. Allegretto

40. 13. Old Dance Tunes. Poco piú vivo

41. 14. Old Dance Tunes. Allegro

42. 15. Old Dance Tunes. Allegro

Suite for Piano, Op. 14, Sz. 62:

43. I. Allegretto

44. II. Scherzo

45. III. Allegro molto

46. IV. Sostenuto

There can’t be many pianists on the current circuit whose fund of experience extends to working with a major twentieth-century master; but of those still recording, Gyorgy Sandor must surely take pride of place. Sandor prepared Bartok’s first two piano concertos under the composer’s guidance and gave the world premieres of the Third Concerto (which he recorded at least three times thereafter) and the piano version of the Dance Suite (he recorded that too, in 1988 for CBS, 9/89 – nla). The present collection is of course Sandor’s second survey of Bartok’s piano music, his first – for Vox (2/62 and 4/62) – having been awarded a Grand Prix du Disque in the mid 1960s. The new set adds a few titles not included before: a 2’18” Andante (rather like a Ravel Valse sentimentale) that was originally intended as the second movement of the Suite, Op. 14 (Sz62), the First term at the piano and a suite of songs and dances that the pianist has arranged (very effectively) from Bartok’s violin Duos. The latter provides a worthy appendage to the Petite Suite that Bartok himself fashioned from the Duos and that Sandor offers here in his second digital Sony recording (his first, reviewed in 9/89, a slightly more delicate affair, is not currently available). Not included is Mikrokosmos – twice recorded by Sandor, first in 1955 (5/93) and then in the early 1960s (4/62), both nla – plus some juvenilia (Scherzos, Fantasies, etc.) and various transcriptions. Much of the more marginal material is due to appear as part of Zoltan Kocsis’s ongoing Bartok piano music survey for Philips, although it should be said that Sandor programmes all the major works – that is, apart from Mikrokosmos.

Many of the new performances are exceptionally fine, even though the passage of time has witnessed something of a reduction in Sandor’s pianistic powers, mostly where maximum stamina and high velocity fingerwork are required – as in the first Burlesque, ”The Chase” from Out of doors and parts of the Improvisations, Op. 20 (Sz75). However, I was astonished at the heft, energy and puckish humour of Sandor’s 1994 recording of the Piano Sonata, a more characterful rendition than its predecessor, with a particularly brilliant account of the folkish Allegro molto finale. Allegro barbaro is similarly ‘on the beam’, while Sandor brings a cordial warmth to the various collections of ethnic pieces, the Romanian Christmas Carols especially. His phrasing, rubato, expressive nuancing, attention to counterpoint and command of tone (sample the 15 Hungarian Peasant Songs) suggest the touch of a master, while his imagination relishes the exploratory nature of the Improvisations, Bagatelles and Miraculous Mandarin-style Studies.

However, many readers will pose the vexed question of textual accuracy, especially with reference to Bartok’s metronome markings. Here Sandor confesses relative freedom. ”It must never be forgotten that Bartok intended these markings simply as approximate guide-lines,” he writes in the context of a fascinating For Children booklet-note, continuing: ”as a performer he himself not infrequently ignored them, as can be heard from his few [sic] surviving gramophone records.” Point taken. And yet Zoltan Kocsis, whose approach acknowledges the ”unusual characters and fine nuances in rhythm and style” of the folk-based works in particular, employs similar insights to quite different ends. ”Two or more recordings of the same piece in Bartok’s performance offer a unique source material for considering what could have been a momentary ‘interpretation’ and what was an essential part of the text of the music… ” writes Laszlo Somfai in the booklet-note for Kocsis’s Philips recording of For Children. Somfai continues: ”In many cases Bartok’s recorded version undoubtedly preserved a revised form compared to the score.” The upshot of this fascinating textual extension surfaces in some significant comparisons, most notably in No. 21 of For Children where Kocsis mimics a playfully augmented bass-line as featured in Bartok’s 1945 broadcast recording (newly available on Hungaroton) and Sandor opts for the ‘standard’ 1943 revision. Compare, also, Kocsis and Sandor in the twelfth Bagatelle, where Sandor clocks up a mere 2’52” as opposed to Kocsis’s 3’57” (although the title-heading ”Rubato” does rather suggest room for leeway). Quite how Bartok would have reacted to having his records used as ‘texts’ is open to question, although I doubt that he would have had anything but praise for Kocsis’s actual playing.

Viewed overall, Kocsis offers the more painstakingly precise reportage of Bartok’s notation and a rather more sharply focused presentation of the music’s multi-faceted rhythmic personality. He is also the more adroit technician, whereas his acute musical intuition guarantees a high level of interpretative individuality. Like Sandor, he approaches the texts (either written or recorded) as guide-lines, and I think it fair to say that in this respect at least, the difference between the two pianists are more a matter of degree than principle. Both give their all wherever Hungarian folk music predominates: sample Kocsis in the first of the Csik Folksongs, Sz35a ((CD) 442 016-2PH, 11/94, track 3) or Sandor in ”Evening with the Szeklers” from Ten Easy Pieces (track 41 on Volume 3 of the present set) and you’d be hard pressed to choose between them.

Which leaves scant space to promote the music’s abundant qualities, be it harmonic or rhythmic innovation, powerful emotion telescoped into a minute time-span (For Children and the various sequences of short pieces), humour (Burlesques), introspection (Dirges), autobiography (the various manifestations of Steffi Geyer’s theme), ethnic variety (Hungarian, Romanian, Ruthenian, Arabic, etc.) or the sheer scope and complexity of Bartok’s piano writing in general. Sandor connects with it all, much as he did 30 years ago, while he now enjoys the added advantage of full-bodied digital sound. His principal rivals are, for the moment at least, severely compromised by being ‘incomplete’: Kocsis has yet to release the majority of Bartok’s major solo piano works and Andor Foldes, whose classic (selective) mono DG survey commemorated the tenth anniversary of Bartok’s death just as Sandor’s commemorates the fiftieth, has so far been represented on CD only by a single selection (6/89 – nla). And although it would undoubtedly be useful to have Sandor’s Vox and American Columbia Bartok recordings re-enter the catalogue, no one, surely, will fail to appreciate the sheer naturalness and perception of this latest undertaking. Intuitive interpreters, especially those who knew and understand the composers they perform, are becoming an increasingly rare breed. In that respect alone, Gyorgy Sandor’s Bartok – be it digital or analogue, Sony or Vox – deserves an honoured place in every serious CD collection of twentieth-century piano music.’