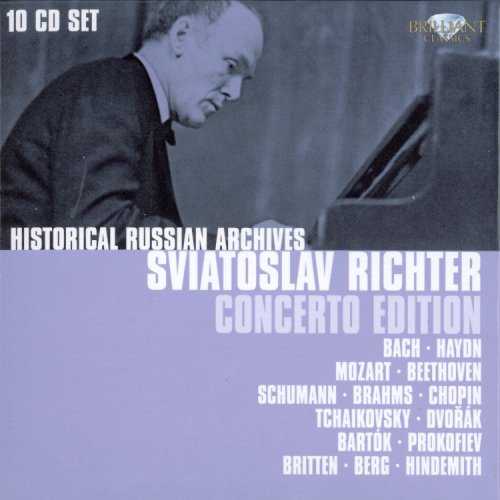

Performer: Sviatoslav Richter

Composer: Johann S. Bach, Wolfgang A. Mozart, Ludwig van Beethoven, Robert Schumann, Peter I. Tchaikovsky, et al.

Audio CD

Number of Discs: 10

Format: FLAC (image+cue)

Label: Brilliant Classics

Size: 2.23 GB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: yes

CD 01

Johann Sebastian Bach

Keyboard Concerto No.1 in D minor BWV1052

USSR State Symphony Orchestra

Kurt Sanderling

Recorded 22.04.1955

Keyboard Concerto No.3 in D major BWV1054

Keyboard Concerto in G minor BWV1058

Students’ Orchestra of the Moscow State Conservatory

Yuri Nikolayevsky

Recorded 19.12.1983

CD 02

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Piano Concerto No.9 in E flat major K271

USSR State Symphony Orchestra

Evgeny Svetlanov

Recorded 25.03.1966

Piano Concerto No.17 in G major K453

Moscow Chamber Orchestra

Rudolf Barshai

Recorded 10.04.1968

CD 03

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Piano Concerto No.20 in D minor K466

Moscow State Symphony Orchestra

Karl Eliasberg

Recorded 20.05.1958

Piano Concerto No.27 in B flat major K595

Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra

Kirill Kondrashin

Recorded 28.03.1973

CD 04

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Piano Concerto No.14 in E flat major K449

Moscow Chamber Orchestra

Rudolf Barshai

Recorded 27.05.1973

Ludwig van Beethoven

Piano Concerto No.3 in C minor Op.37

Moscow Youth Symphony Orchestra

Kurt Sanderling

Choral Fantasy in C minor Op.80

USSR State Radio Symphony Orchestra and Chorus

Kurt Sanderling

Recorded 22.03.1952

CD 05

Robert Schumann

Piano Concerto in A minor Op.54

USSR State Symphony Orchestra

George Georgescu

Recorded 17.04.1958

Pyotr I’lyich Tchaikovsky

Piano Concerto No.1 in B flat minor Op.23

Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra

Kirill Kondrashin

Recorded 09.04.1968

CD 06

Johannes Brahms

Piano Concerto No.2 in B flat major Op.83

USSR State Symphony Orchestra

George Georgescu

Recorded 17.04.1958

Richard Strauss

Burleske in D minor

USSR State Symphony Orchestra

Gennady Rozhdestvensky

Recorded 18.12.1961

CD 07

Frédéric Chopin

Piano Concerto No.2 in F minor Op.21

USSR State Symphony Orchestra

Evgeny Svetlanov

Recorded 22.12.1966

César Franck

Les Djinns

Moscow Youth Symphony Orchestra

Kirill Kondrashin

Recorded 30.12.1952

Joseph Haydn

Piano Concerto in D major Hob.XVIII/11

Minsk Chamber Orchestra

Yuri Tsiryuk

Recorded 19.11.1983

CD 08

Antonín Dvořák

Piano Concerto in G minor Op.33

Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra

Evgeny Svetlanov

Recorded 29.05.1966

Sergei Prokofiev

Piano Concerto No.1 in D flat major Op.10

Moscow Youth Symphony Orchestra

Kirill Kondrashin

Recorded 31.05.1952

CD 09

Bela Bartók

Piano Concerto No.2 in F minor Op.21/Sz95

USSR State Symphony Orchestra

Evgeny Svetlanov

Recorded 06.05.1967

Benjamin Britten

Piano Concerto No.1 in D major Op.13

USSR State Symphony Orchestra

Evgeny Svetlanov

Recorded 28.05.1967

CD 10

Alban Berg

Chamber Concerto for piano, violin and 13 wind instruments

Oleg Kagan, violin

All-Union Radio and TV Large Symphony Orchestra

Rudolf Barshai

Recorded 09.04.1972

Paul Hindemith

Kammermusik No.2

Moscow Conservatory Orchestra

Yuri Nikolayevsky

Recorded 22.05.1978

richter_concerto_edition02.rar – 250.5 MB

richter_concerto_edition03.rar – 259.0 MB

richter_concerto_edition04.rar – 271.2 MB

richter_concerto_edition05.rar – 212.3 MB

richter_concerto_edition06.rar – 238.7 MB

richter_concerto_edition07.rar – 235.2 MB

richter_concerto_edition08.rar – 191.7 MB

richter_concerto_edition09.rar – 209.3 MB

richter_concerto_edition10.rar – 228.8 MB

A Fine Find

Sviatoslav Richter- Concerto Edition (Historical Russian Archives) [Box Set]

For years I have longed to hear two Richter concerto recordings, and one of them is on this huge 23-concertos-in-all; it is the Haydn D major Concerto 11 HOB XVIII/11.** So I bought the collection, only to discover the Haydn is listed as one of a number of other previously unreleased Richter recordings, all of them with live audiences, and many of them quite different versions than the ones I already own.

The previously unreleased recordings here are Bach 1, 3, 7; Mozart 9, 17, 20, 27; Beethoven 3, Choral Fantasy; Tchaikovsky 1; Chopin 2; Dvorak 2; Prokofiev 1; Britten D major Op 13; Haydn 11; Prokofiev 1, Tchaikovsky 1. I mark them an asterisk.

Those previously released are Mozart 14; the Schumann; Brahms 2; Strauss Burlesque; Franck Les Djinns; Bartok 2; Berg Chamber; Hindemith 2,

What you get from Sviatoslav Richter is that rare quality: power – power which always means power to spare – power which always provides that rare quality in an artist: breadth, latitude.

Hurray, first we are given a bunch of Bach recordings! No. 1 BWV 1052 [USSR State S.O. Kurt Sanderling 22 Aril 1955*] No 3. BWV 1054 [Students’ O. of Moscow State Conservatory 19 December 1983*] G minor BWV 1058, same band, same date*].

The Bach recordings are interesting, and none more so than the No 1 in D minor which is incontinently slow, for one is used to the famous version we all heard first on LP with the Prokofiev 1 on the verso and which captures one of Bach’s major compositional characteristics, his drive. That force is rather lost here. The other two concertos reveal Richter’s amazing ability to play silence. No other pianist commanded such a talent for allowing for and filling to the brim with meaning, pauses. To my mind the version of No 3 in D major BWV 1054 with Yuri Bashmet conducting on TELDEC captures the greatness at its greatest of Bach and Richter in partnership. You are faced with a towering mystery and are grateful for the opportunity. But that may be because that is the first version of it I ever heard, and fell I love for the first time, and we all know what that means.

Five Mozart Concertos are included, two of them first releases. No 9 K271 [USSR S.O. Evgeny Svetlanov 26 March 1966]; No. 14 K449 [Moscow Chamber O. Rudolf Barshai 27 May 1973]; No 17 K453 [Moscow S.O. 10 April 1968]; No 20 K466 [Moscow State S.O. Karl Eliasberg 20 May 1958*]; No. 27 K595 [Moscow P.O Kirill Kondrashin 28 March 1973*].

The Mozart Concertos are not music Richter had the inside dope on. And besides, except for the middle movements, Mozart tends to produce boilerplate in his concertos. His busy lazy habit is to grandly develop musical content whose paltriness or infantility will not sustain such grandeur. (If you want to hear Richter play Mozart, fabulously get all his recordings of the Mozart violin sonatas with Oleg Kagan, a musical marriage unique in classical recording.) The vulgarity of Mozart is hard to elude – all those spangles – and Richter does not even grasp it, so it escapes him completely. And his playing is, as well, as his wife would say, occasionally harsh – Mozart, whatever his defects, was never unkind. Indeed Mozart is at times more fun than a cradlefull of puppies, but Richter, who is not a humorist, does not get that either. Hardly anyone does. Most musicians take Mozart to be Very Serious Classical Music. Fiddlesticks. Mozart is primarily an entertainer. Richter is not. Mozart cares about his audience; Richter does not. Richter cares only about the music. Mozart was also an entertainer. Of this Richter knows nothing. It is no wonder Richter did not get him – except here in those slow movements, when all, all, all, is heaven.

Here we have Beethoven No 3 [Moscow Youth S.O., Kurt Sanderling 22 March 1952*] and The Choral Fantasy Op 80 [same band, conductor, and date*, though I have this on another label.]

He was not a great Beethoven player either, because his tone is percussive. Beethoven requires a round sound; the music has depth not altitude; you don’t go to Beethoven for the exalted even when you do; you go for the psychological veracity of the sudden inner movement of the psyche, depth. This surprised at the time, and it still surprises. I heard Richter’s debut concerts in New York and met him then. A lovely great big red-faced man with huge hands and an ill-fitting cutaway; he was very welcoming to me. It was after the all-Prokofiev concert. On opening night he played Beethoven such as you had to be there to believe (recordings exist; my Bravos are on them). The Appassionata was played with a power titanic. Well, Beethoven was a virtuoso pianist requiring a virtuoso pianist. And this one brought the house down. Rubenstein said Richter could do with a piano what he had never known could be done. The Carnegie Hall audience was dumbstruck. And yet. And yet Beethoven’s piano music is not written for a pianist of diabolical and celestial power (such as Richter’s); lesser pianists can play it more greatly. It was great playing; it was not great Beethoven. The performance was one of astounding intensity, but Beethoven is a composer who is not interested in intensity. In Beethoven intensity is impertinent. Beethoven’s solo piano music identifies the person who hears it, not the person who plays it. That is its revolution and requirement. This was not really within Richter’s gift. Through no fault of his, his inner instrument was not the right one for it, nor was his predilection, which was purely musical, for Beethoven is not just about music.

The Brahms Concerto [USSR State S.O. George Georgescu, 17 April 1958] is probably one Richter would have said he preferred to the great famous Chicago S.O. with Leinsdorf, but Richter’s sense of his own performances was often nutso. The violins here are thin, and the orchestra does not have the body of the Chicago band which Brahms’ magisterial sound requires, but the reading is honorable, and Richter’s solo passages and passages accompanied by fewer instruments are exquisite and quite different from what you find in the Chicago version.

On the same disc is the Strauss Burlesque [same orchestra, Gennady Rozhdestvensky 1961.] One wonders why Richter decided to play the Strauss Burlesque. Perhaps its coldness suited his aloof temperament. He remarked at the end of his life that he had missed playing Scarlatti – but, oh, I wish he had learned instead, and instead of the Strauss, the concertos and sonatas of Baldassaro Galuppi – a perfect composer for him in terms of rhythmic affinity and power.

Richter’s playing of the Bartok Concerto 2 is stupendous and frightening. When cold meets cold, as in this case, the piano burns hot ice. [May 1967 USSR State O., Svetlanov]. And later in May that year, the same personnel in a “previously unreleased” (although I have it on Russian Revelation) Britten 1*. This piece is played with great application by the master. If not exactly in Britten’s line, the piece has lots of oomph and big splashy movements which Richter and everyone has a firm grasp on and which are played by him wholly for their formal and classical restrictions and releases. Its modernism takes care of itself. You couldn’t ask for a better rendition.

Richter’s particular and powerful and inbred sense of rhythm makes him an especial master of those composers in whom rhythm is pronounced – rhythm: the inhalation and exhalation of the music – not Beethoven, not Chopin – but Rachmaninoff, Gershwin, and Schumann. And so we are given the live recording of Schumann’s Op 54 [17 April 1958 Georgescu conducting the USSR State S.O.] taken at a good clip, but played with great tenderness and intimacy still, and dynamism like no other.

Of the Tchaikovsky 1, have three different conductors playing it with him, I like them all and I like this one very much. It’s a piece a pianist can get washed up on after a while. Richter played it 50 times in public from 1941 on, then stopped. It would seem that he had nothing more to say, and the public had nothing more to hear: Tchaikovsky wax build-up. People think they’ve heard it. Too bad, because it is maybe the greatest of all concertos and as Richter said, along with the Dvorak 2, the most difficult to play. It is a work of great majesty. And Richter, an artist of royal inner bearing, carries it like a robe on his broad shoulders. This [9 April 1968 Moscow P.O, Kondrashin*] is the most gracious of all the versions. Why listen to anyone else.

Richter reinvented the Dvorak 2. This recording [29 May 1966, Moscow P.O, Svetlanov*] has people coughing right into their coffins. It may be that they wanted Richter to pay attention to them, which was not his way. His platform manner was always odd, with that petulant walk and head cocked away from the crowd. He didn’t want to pay attention to the audience or the audience to him; he wanted the audience to pay attention to the music. Anyhow, the writing of the opening of the concerto is banal. You think it would be better used in one of his trios or dumki – but then it takes off and we get what Dvorak does best. All the furniture is beautifully managed and placed around. And Richter’s playing of the andante is supernal. It is night music. So close your eyes while listening to it.

Prokofiev 1* [Moscow Youth S.O. Kondrashin, 31 May 1952*] Richter owns it. No one else owns it. This may be the same recording I have on LP, one of the first records sifting West to the USA in the late 50s. Bach 1 on the other side, if I recall. I still have it somewhere. Anyhow, the thrill has not gone. Listen to Richter come down just a mille-second ahead of the beat, as Margot Fonteyn used to do. It brings the whole thing up to a rare, inherent, and necessary excitement. And, musically, it is right on the money.

Chopin 1 [USSR State S.O., Svetlanov 22 December 1966*] As is the custom with Richter, he adds nothing, and by doing so subtracts nothing. However, keeping in mind that Schubert is a composer whose heart is broken, while Chopin is a composer who is out to break your heart, one longs to be touched. It is said of Richter that he is the pianist by whom one should hear a piece played before you hear it played by any other. Sometimes it is true of him that one never wants to hear him play it again, because for Richter the music only has content, never the composer. I wonder if this isn’t sometimes a mistake. He is nowhere near being a good Chopin player. Sometimes one has to be in love with the music to play it, and sometimes also with the composer, as with Chopin: his fragrance, his towering temper, his grief, his harmonics, his classicism, his masculinity, and the long eyelashes of his seductiveness. So while Richter’s Chopin playing may be great playing, it is not great Chopin. To contradict all this, however, at the great Sophia Concert after Mussorgsky and Liszt and Schubert, he gave a Chopin prelude. On that day Richter said he did the greatest playing of his life, and nobody listened. Listen to it now. Or just listen to the prelude. Has it ever been played more perfectly, more justly! Don’t answer.

César Frank’s Les Djinns [Moscow Youth S.O. Kondrashin 30 December 1952] He is said to have performed this concerto only twice. What an odd piece! And to go to all the trouble to learn it – like the Scriabin concerto. He was a great Franck player, like Gieseking. It is a piece which does not invite re-listening, but it does require it. It is written in the grand 19th Century style that eventually became silent movie music, full of waterfalls and torrents and storms at sea and mountain heights draped in blizzards.

Alban Berg’s Chamber Concerto [All-Union Radio and TV Large S.O., Rudolph Barshai 9 April 1972] is a cranky piece, and Richter has no competition in performance history or contemporary styles to distract him from delivering the goods. As soon as things opened up in Russia, he involved himself in modern music, and what a gift he brings. Here’s a good case of absolute music absolutely performed as music and nothing else besides. He has no fear in performing it. And why is that? A towering genius is a structure one has to inhabit, and a technical prowess is a talent nascent and developed, yes, but Richter was also a musician of great musical modesty. He is never showy. Every musical line is rendered for itself alone, no “personality” involved. How about that?

Hindemith’s Chambermusic Concerto No 2 [Moscow Conservatory O. Yuri Nikolayevsky 22 May 1978] is one of many Richter promotions of this composer. Again, he is delivering the music without context, exactly as written. And what a gift to us it is. There are not many composers of classical music who are inherently humorous. Rossini is a famous example and Hindemith is another. See if you don’t agree.

Richter loved Haydn. He made revolutionary recordings of his sonatas. And here he exposes an act of criminal negligence in being guilty of not playing more of the Haydn Concertos, for this is one of his greatest performances. He gives the Concerto 11 in D HOB XVIII/11 [Minsk Chamber O., Yuri Tsiryuk 19 November 1983*] a big reading. There is no immolation on the poniard of period style. Richter takes hold of the concerto and delivers it fully and modernly and with great musical compassion and fullness and a thoroughgoingly gutsy respect for the humor of the piece in every passage. Haydn was the great master of musical management; he knew exactly what an instrument or an orchestra should do and could do when and where and how much. This resplendent talent Richter understood and meets head on. As Richter said of him Haydn is always fresh, and Richter has you lean forward into the gift of that spontaneity. He’s not picayune or dainty. He gives Haydn the revelation of the grand style. You can feel the music surge with Richter’s timing, his refusal to metronome it, yet his delight in playing it exactly as written. Richter is the great master of modulation, and here you have it caress and open up the music for you. You marvel at the beauty of Haydn’s piano writing, and that is because Richter knows it better than anyone. You have never heard Haydn played until you hear Richter play. It is reason enough to buy, as I did, all the other 22 Concertos besides.

The program notes are eccentric, thank goodness, and excellent. If a couple of the concertos are not first releases, but so what? The intention is genuine, and the collection is wonderful, and, of course, hugely inexpensive.

Richter is represented at all ages here, but the lovely thing is to often hear him when he was young and setting the musical world on its ear – ears. So the versions from the 50s and 60s are to be treasured and wondered over. His power, his verve, his daring, his consummate musical hold, his unmatched discretion, his honoring of detail, his tone from what realm of heaven, his range of hand, his drive, his stillness, his ability to make all sorts of distinctions between his left and his right hand, his architectonic hold, his refusal to sully a piece with a particular emotion, the vast repertory he brought us – it is no wonder he was voted the greatest musician of the 20th Century.

Such a denomination is, on the other hand, inconsequential, for who is to say, except the voters who said so? All of the attributes listed above mean nothing in such an election. The only thing that matters is the musicality itself. And that matters everything. And that’s why he won. And that is why you listen to Richter and must listen to him or be impoverished.

* means first CD release of the concert, but not necessarily the concerto.

**. (The other one being the Saint-Saens 2nd, of which I have seen only a Technicolor snatch.)

thanks very much, these are fantastic recordings.

Thanks a lot sir.

Thank You!!!

Much appreciated!