Composer: Charles-Valentin Alkan, Ferencz Liszt

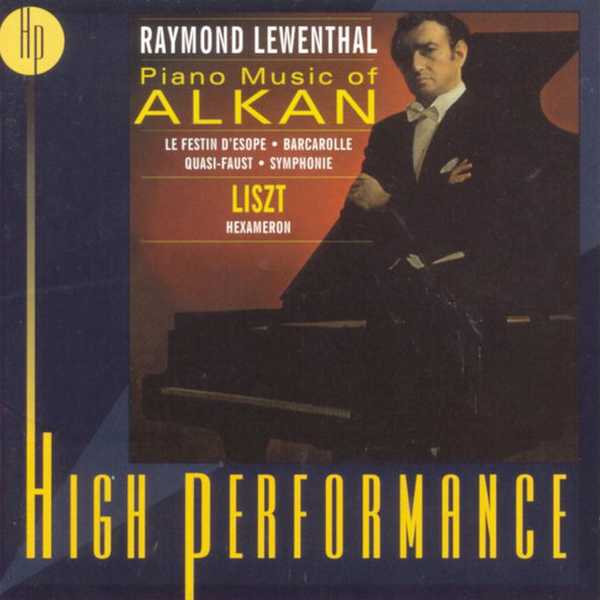

Performer: Raymond Lewenthal

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: RCA

Catalogue: 09026633102

Release: 1990

Size: 293 MB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: cover

Alkan: Etudes in All the Minor Keys, Op. 39

01. No. 12, Le Festin d’Ésope

Alkan: Barcarolle, Op. 65

02. No. 6

Alkan: Grande Sonate, Op. 33

03. Quasi-Faust II.

Alkan: Etudes in All the Minor Keys, Op. 39

04. Symphonie: I. Allegro moderato

05. Symphonie: II. Marche funèbre

06. Symphonie: III. Menuet

07. Symphonie: IV. Finale

Liszt: Hexaméron, S392

08. Introduction

09. Theme

10. Variation I

11. Variation II

12. Variation III

13. Interlude I

14. Variation IV

15. Variation V

16. Interlude II

17. Variation VI

18. Interlude III

19. Finale

Raymond Lewenthal: Piano Music of Alkan & Liszt consists of recordings by legendary pianist Raymond Lewenthal made for RCA-Victor in 1965 and 1966. These recordings were the touchstone of the Romantic Revival in the 1960s that Lewenthal spearheaded, but whose full effect would not be apparent until a couple of decades hence. Despite many requests for reissues of this material on CD, low original sales figures prevented BMG from seriously considering it until 1999, when it released this program in a limited-edition High Performance series. It wound up being one of the very last reissues BMG put out before closing down its classical division, and it was followed three years later by a licensed version of the exact same program that appeared on the independent label Élan. What separates the Élan issue from the BMG, other than that the BMG is a bit more difficult to find, is four bits; Élan’s CD is a 20-bit remaster, whereas BMG’s High Performance reissue is 24. Élan’s booklet is a little more deluxe and detailed than that by BMG, which mainly includes the original album notes, written by Lewenthal himself.

Lewenthal certainly was “legendary,” a larger than life figure, just as mysterious and off-center as the composers he championed. In the 1960s, Lewenthal resurrecting from the dead the obscure, hyper-virtuosic literature of the nineteenth century at a time when the classical music establishment was so absorbed with contemporary music it hardly cared. Two decades after Lewenthal’s death it is easy to see how important his contribution was, as practically all of the then-unknown literature of Alkan, Liszt, Henselt other composers he advocated has been recorded, some of it multiple times. For pianists such as Marc-André Hamelin, the Lewenthal diet, once regarded by many as a hopelessly lost cause, is more like a main course.

Whatever way one obtains this, Lewenthal’s readings of these works of Alkan and Liszt are essential. They are not necessarily “note perfect”; sometimes Lewenthal the editor overrules the composer, for example in the “fleas” variation of Alkan’s Le festin d’Ésope Lewenthal takes the passage forte, as opposed to Alkan’s specified pianissimo — musically it makes more sense at forte, but fleas are tiny little things and perhaps that’s why Alkan made it pianissimo. Lewenthal sometimes has tiny, barely noticeable finger slips and other vagaries of performance that would not be commonly found in the playing of, say, Hamelin. However, Lewenthal’s passionate playing, not to mention his sense of dedication to this music, is intense and should be heard by anyone who loves the piano.