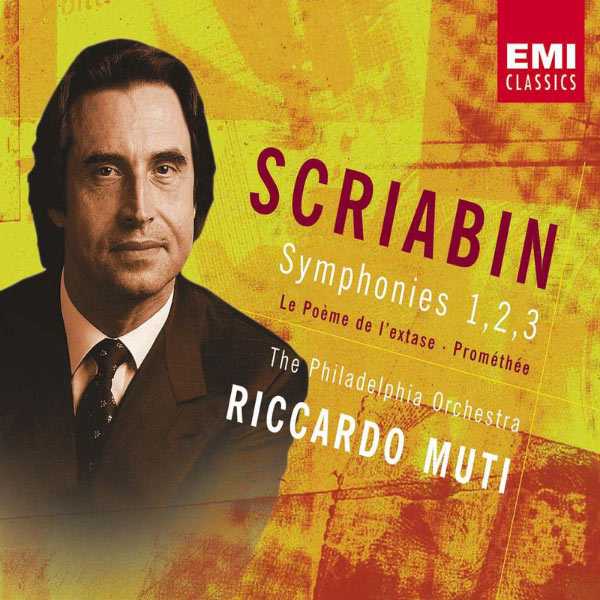

Composer: Alexander Scriabin

Performer: Stefania Toczyska, Michael Myers, Frank Kaderabek, Westminster Choir, Dmitri Alexeev, Choral Arts Society of Philadelphia

Orchestra: Philadelphia Orchestra

Conductor: Riccardo Muti

Number of Discs: 3

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: Warner

Catalogue: 5677202

Release: 1991

Size: 787 MB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: cover

CD 01

Symphony No. 1 in E Major, Op. 26

01. I. Lento

02. II. Allegro dramatico

03. III. Lento

04. IV. Vivace

05. V. Allegro

06. VI. Andante

CD 02

Symphony No. 2 in C Minor, Op. 29

01. I. Andante

02. II. Allegro

03. III. Andante

04. IV. Tempestuoso

05. V. Maestoso

06. Symphony No. 4, Op. 54 “Poème de l’extase”

CD 03

Symphony No. 3 in C Minor, Op. 43 “Divine Poem”

01. I. Lento & II. Luttes

02. III. Voluptés

03. IV. Jeu divin

04. Symphony No. 5, Op. 60 “Prometheus”

Had he lived into the age of recordings instead of dying in 1915, Scriabin would no doubt have relished the idea of listening to a complete cycle of his own symphonic works. Of course, had he lived into the age of recordings, Scriabin would have added only one other work to his oeuvre — the Mysterium for soloists, choruses, and orchestras along with actors, dancers, perfumers, and light projector operators plus percussionists striking bells suspended from balloons — because, according to the composer, at the conclusion of the work’s premiere, the world as we know it would have come to an end with the transfiguration of humanity, thereby foreclosing further opportunities for listening to recordings. Thus, deprived of transcendence, we will have to content ourselves with the more circumscribed ecstasy of Scriabin’s extant symphonic works. While some listeners would argue that Evgeny Svetlanov’s cycle with the USSR Symphony from the ’60s delivered the more authentic “Scriabin experience,” most listeners would agree that Riccardo Muti’s cycle with the Philadelphia Orchestra from the late ’80s and early ’90s delivered better-played and better-sounding performances. Of course, the Philadelphia at that point in Muti’s tenure as music director was only a marginally more polished orchestra than the USSR Symphony under Svetlanov, and EMI’s early digital sound was only slightly less distant than Melodiya’s Russian stereo sound, so these distinctions are not necessarily decisive. More persuasively, Muti’s interpretations, like the works themselves, grow grander and more glorious as the cycle progresses. Muti’s First is unbelievably massive; his Second is incredibly monumental; his Third, subtitled “The Divine Poem,” is unthinkably egomaniacal; his Fourth, called “The Poem of Ecstasy,” is unimaginably monomaniacal; and his Fifth, called “Prometheus — The Poem of Fire,” is inconceivably megalomaniacal. Scriabin, had he lived to hear it, would have loved it.