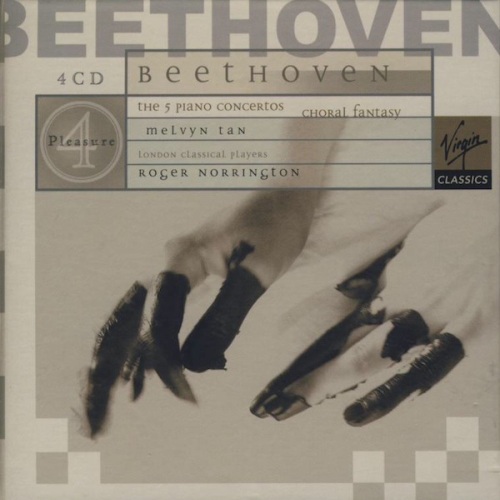

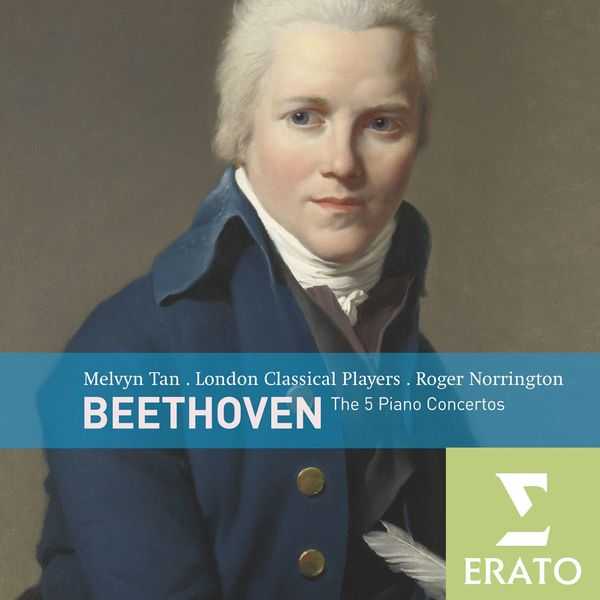

Composer: Ludwig van Beethoven

Performer: Melvyn Tan

Orchestra: London Classical Players

Conductor: Roger Norrington

Number of Discs: 2

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: Erato

Catalogue: 95220142

Release: 2008

Size: 513 MB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: cover

CD 01

Concerto pour piano n° 2 en si bémol majeur, op. 19

01. I. Allegro con brio

02. II. Adagio

03. III. Rondo. Molto allegro

Piano Concerto No.1 in C major, op. 15

04. I. Allegro con brio

05. II. Largo

06. III. Rondo. Allegro scherzando

Piano Concerto No.5 in E flat major Op.73 -‘Emperor’

07. I. Allegro

CD 02

Piano Concerto No.5 in E flat major Op.73 -‘Emperor’

01. II. Adagio un poco mosso

02. III. Rondo. Allegro

Concerto pour piano n° 3 en ut mineur, op. 37

03. I. Allegro con brio

04. II. Largo

05. III. Rondo. Allegro

Concerto pour piano n° 4 en sol majeur, op. 58

06. I. Allegro moderato

07. II. Andante con moto

08. III. Rondo. Vivace

Recorded in three sessions between 1988 and 1989 for Virgin Classics, Melvyn Tan and Roger Norrington’s performances of Beethoven’s five piano concertos produced something of a sensation when they were first issued. Purists who valued the big tone of the modern concert grand and the big sound of the modern symphony orchestra were dismayed at the tinkly tone of Tan’s fortepiano and the scrawny sound of Norrington’s London Classical Players. But true purists — those who averred the path to aesthetic truth lay through the use of period instruments and historically informed performance practices — found Tan’s fortepiano refreshingly subtle and nuanced and Norrington’s orchestra bracingly clear and colorful.

Reissued 20 year later on a Virgin Veritas two-disc set with the Fifth Concerto split between discs, Tan and Norrington’s Beethoven concertos no longer sound especially tinkly or scrawny. True, Tan’s lean, light instrument lacks the raw power of a concert grand and Norrington’s clean, bright orchestra lacks the mass and weight of a symphonic orchestra. But for ears grown accustomed to such things after two decades of historically informed performances on period instruments, these are neither negative nor positive qualities, but merely interpretive choices.

Twenty years later, a more important concern for all listeners is the quality of the performances themselves. For some, Tan’s balletic rhythms and acrobatic virtuosity and Norrington’s buoyant tempos and primary colors will prove entirely welcome. For others, the performers’ perceived want of gravitas in slow movements and profundity in the later concertos may be off-putting. Captured in close, cool digital sound, it is probably wisest to sample Tan and Norrington’s performances first.