Composer: Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, Johann Sebastian Bach

Performer: Makoto Nakura, Satoshi Sakai

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: American Modern Recordings

Catalogue: AMR1044

Release: 2016

Size: 219 MB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: yes

01. Bach JS: Toccata & Fugue in D minor, BWV565

02. Bach CPE: Twelve Variationen über die Folie d’Espagne, Wq118 / 9 / H263

Bach JS: Flute Partita in A Minor, BWV 1013 (Arr. M. Nakura for Vibraphone)

03. I. Allemande

04. II. Corrente

05. III. Sarabande

06. IV. Bourree Anglaise

Bach JS: Cello Suite No. 6 in D major, BWV1012

07. I. Prelude

08. II. Allemande

09. III. Courante

10. IV. Sarabande

11. V. Gavotte I-II

12. VI. Gigue

Bach JS: Sonata for solo violin No. 1 in G minor, BWV1001

13. I. Adagio

14. II. Fuga

15. III. Siciliana

16. IV. Presto

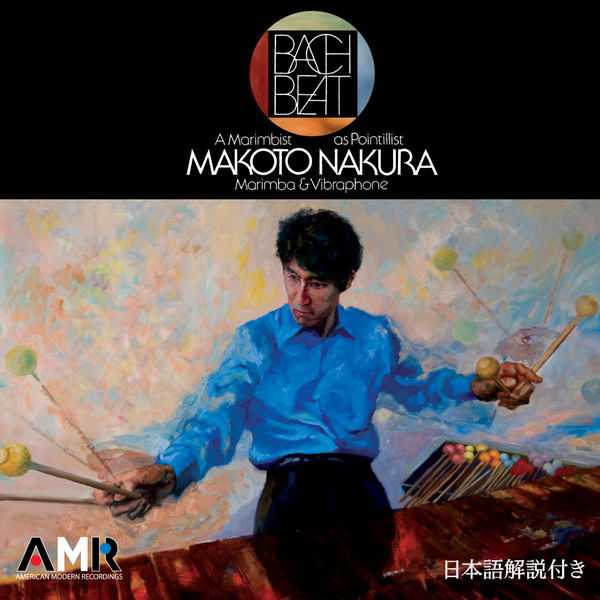

BACH BEAT: A Marimbist as Pointillist performed by Makoto Nakura on Marimba & Vibraphone. Bach’s music is the highest mountain for all musicians to climb. Even though Bach didn’t write any pieces for the marimba, I have not spent a single day without playing his music from my own transcriptions of Bach’s works for violin, cello, flute, lute, and keyboard. One day on a subway train in New York, I ran into a friend who is a violinist in a famous string quartet. “So, what pieces have you been ‘stealing’ from other instruments these days?” he enquired. Being newcomers to classical music, marimbists have been working hard to create new repertoire by commissioning new works as well as transcribing works for other instruments. I almost retorted that perhaps he wouldn’t understand how difficult it is to have a limited body of repertoire, because many great composers have written wonderful pieces for string quartet. But, instead of saying that, I just answered “Maybe Bach’s Flute Partita.” Then, I was glad to hear him say “I see. Bach’s music is so pure that it wouldn’t lose anything even if it were played on a different instrument.”

Since Bach’s music can engage the mind so intensely, it almost lets us forget which instrument is being played. Many composers write pieces in a way that utilizes the characteristics of instruments. I would call this a “concrete” way of composing. But, Bach’s music sounds as if he wove notes from a more “abstract” world. This is when the word “pure,” that my violinist friend used, begins to resonate. The reason I want to play Bach on the marimba comes to this – I would like people to listen to the music I am playing rather than to what instrument I am playing. Bach’s music has taught me so many things… When I was a child, my ears were accustomed to listening to a pretty melody with an accompaniment where we can clearly hear a dominant figure above the others. But, Bach’s music brought me polyphony, something much more complex. I was excited to follow many melodies proceeding simultaneously. Each melody has equal importance and the interaction among the melodies moves the music forward. Much later I started to realize that many lines weave organic, three dimensional structures. The structures appear before you, each line interacting with others, gradually changing their shapes-

This is the brilliant artistic moment that polyphonic music gives us. I will always remember a concert I gave in chilly Iowa early in my US career. It was on that stage that I began to see how I, as a performer should communicate with the audience, and that happened while I was playing the G Minor Fugue. I think performers have to be creators too, and I want to perform as if I were collaborating with composers on the stage. To do that, I thought I had to feel deeply what each note means to me. When each note starts having some special meaning for me – it can be a color, scent, or even a word from a poem- maybe my playing can reach the furthest corner, and touch the deepest part of people’s minds. I wouldn’t have been able to keep playing Bach in concerts if I hadn’t been supported by many encouraging comments from the audiences. Comments such as “I couldn’t hold back my tears while you were playing the Sarabande” make me feel very humble when I think about the great power of the music and how deeply this music affected another person.

However, it is when I play Bach that I become the target of criticism. Playing Bach requires not only the cleanest technique, but also the depth of your intelligence, emotion, and mental capacity. It is an occasion when you reveal your musicianship, the qualities you possess as a ????????performer, and ultimately, your humanity. Also, as each listener often has his own criterion of ideal Bach performance, it becomes a challenge for listeners, as well, to accept playing that differs from what they are used to.Invariably, the criticism focuses on marimba tremolo technique. Since the marimba’s sound fades away quickly, when we want to play long notes, we always use the tremolo technique which consists of hitting the same note in rapid repetition. Some listeners find tremolos disturbing to the extent that they find it difficult to hold on to the context of the music I am playing. Others, although they find tremolos surprising at first, gradually see that the notes of a tremolo become the points of a line. Some people have said they found the lyrical quality of each line, and those are the people who give me hope. In piano pedagogy, they also put a particular emphasis on how you make a line by playing a series of notes. Although the piano’s sound stays sustained much longer than the marimba’s, it still cannot match the sustained sound created by voice, strings and wind instruments.

While studying at the Royal Academy of Music in London, I learned from a piano professor that if I listened to the line intently and put utmost concentration on it, a series of points would start to sound like a line. Would it be possible to do the same thing on the marimba? Well, sometimes it succeeds, and sometimes it doesn’t. When I play chamber music with string and wind players, the places I play tremolos tend to cause problems. My colleagues have often asked me “Why don’t you just quit the tremolos?” For them tremolos sound too percussive, and simply too busy to make a beautiful lyrical line, and spoil the sustained sound they are making. When I commission new pieces from composers, we al- ways discuss how we can use tremolos effectively in the pieces. Some composers remain unconvinced by the possibility of tremolos, and they prefer to exclude them completely. On the other hand, a number of composers have written me wonderful music, taking advantage of the unique expression tremolos make. This fact gives us, marimbists, so much hope. Some time ago I was playing a marimba concerto with an orchestra. The whole string section was playing smooth melody lines, and I joined them with my tremolo line.

But, what was this sudden sense of inadequacy that hit me at that time? In the tense soundscape of lines created by many string players, my tremolos sounded misplaced as if I were throwing distorting pebbles into the lines. Is it really feasible to make a line with tremolos? It was only when I encountered the paintings of French pointillist Seurat that I recovered my faith in tremolos. Before then, I thought I had no other choice but to play tremolos for long notes, and often did so reluctantly. But, pointillist painters like Seurat dare to choose points, in order to simulate lines. On their canvases we see somewhat lonely images straying between dreams and the real world. Seurat’s paintings struck me with the revelation that this unique expression cannot be created by using real lines. I want to bring about the same effect in music by using tremolos. If I describe sustained sound as a brush stroke to paint the real world, perhaps the many points of tremolos could become molecules to draw the surreal world… And so I have called this CD “A Marimbist as Pointillist.” The singing of a lone bird in a deep forest cannot reach anyone’s ears. There is an impossible gap to cross over between points and lines. The loneliness hovering in the crevice of reachable and unreachable, akin to the bird singing, spreads over my canvas. Makoto Nakura December, 2007 in New York City