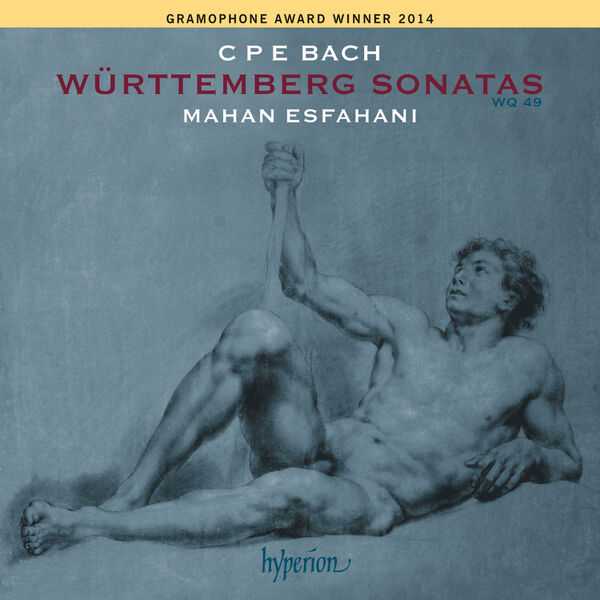

Composer: Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach

Performer: Mahan Esfahani

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: Hyperion

Catalogue: CDA67995

Release: 2014

Size: 1.43 GB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: yes

Keyboard Sonata in A minor, Wq. 49 / 1 (H30) ‘Württemberg Sonata No. 1’

01. I. Moderato

02. II. Andante

03. III. Allegro assai

Keyboard Sonata in A flat major, Wq. 49 / 2 (H31) ‘Württemberg Sonata No. 2’

04. I. Un poco allegro

05. II. Adagio

06. III. Allegro

Sonata in E minor, H33

07. I. Allegro

08. II. Adagio

09. III. Vivace

Keyboard Sonata in B flat major, Wq. 49 / 4 (H32) ‘Württemberg Sonata No. 4’

10. I. Un poco allegro

11. II. Andante

12. III. Allegro

Keyboard Sonata in E flat major, Wq. 49 / 5 (H34) ‘Württemberg Sonata No. 5’

13. I. Allegro

14. II. Adagio

15. III. Allegro assai

Keyboard Sonata in B minor, Wq. 49 / 6 (H36) ‘Württemberg Sonata No. 6’

16. I. Moderato

17. II. Adagio non molto

18. III. Allegro

Hyperion is delighted to present the debut recording of the wonderful young harpsichordist Mahan Esfahani. He was the first harpsichordist to be named a BBC New Generation Artist or to be awarded a fellowship prize by the Borletti-Buitoni Trust.

Here Mahan Esfahani has recorded CPE Bach’s six ‘Württemberg’ sonatas, which were written in 1742–3 and published in 1744, and his thrillingly intense performances make the best possible case for this dramatic, beautifully written, endlessly imaginative but for some reason under-performed music. The sonatas range stylistically from initial stirrings of Sturm und Drang in keyboard music to sublime imitations of the human voice, with nods to the High Baroque and the idiom of CPE Bach’s more famous father. Mahan writes in his booklet notes that ‘Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach makes the most combative statement possible to assert his new musical language’.

The Württemberg Sonatas of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach were harpsichord pieces, composed in 1742 and 1743. As Iranian-born harpsichordist Mahan Esfahani points out in his booklet notes (which are elegant, enthusiastic, informative, personal, and altogether more appealing than almost any comparable example), this is a time thought of as part of the High Baroque, but J.S. Bach’s eldest son was already definitively going his own way. Occasionally there is a nod to his father’s style: the finale of the Sonata in B minor, H. 36, is essentially a two-part Invention like those of the elder Bach, and many movements begin with squarish, quasi-orchestral Baroque figures. But C.P.E. delights in demolishing these with what would become his trademark abrupt leaps, and Esfahani is wonderfully alert to the humor in these. The slow movements, with dotted figures being stretched out to chromatic extremes, are especially reminiscent of Haydn, who pointed to C.P.E. Bach as an influence in the first part of his career even though his training was primarily Italian. Another attraction is Esfahani’s harpsichord, constructed by Czech builders after Berlin models from the early 18th century. From the notes one learns that “the decision to have the 4′ strings plucking more toward the midpoint of the string than the other registers results in a flute-like solo 4′ register and 8′ and 4′ combinations that have a particularly singing quality.” The instrument sounds almost like a fortepiano at times, and it is capable of realizing the dynamic effects that are written into Bach’s music. This is a recording that engages itself unusually deeply with issues that audiences in the 18th century would have found relevant.