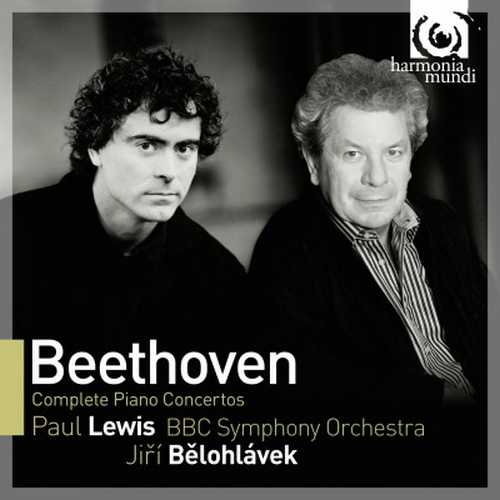

Composer: Ludwig van Beethoven

Performer: Paul Lewis

Orchestra: BBC Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: Jirí Belohlávek

Audio CD

Number of Discs: 3

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: Harmonia Mundi

Size: 1.52 GB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: yes

CD 01

Piano Concerto No. 1 in C Major, Op.15

01. I. Allegro con brio

02. II. Largo

03. III. Rondo. Allegro scherzando

Piano Concerto No. 2 in B flat major, Op. 19

04. I. Allegro con brio

05. II. Adagio

06. III. Rondo. Molto Allegro

CD 02

Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor, Op. 37

01. I. Allegro con brio

02. II. Largo

03. III. Rondo. Allegro

Piano Concerto No. 4 in G major, Op. 58

04. I. Allegro moderato

05. II. Andante con moto

06. III. Rondo vivace

CD 03

Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat Major, Op. 73 ‘Emperor’

01. I. Allegro

02. II. Adagio un poco mosso

03. III. Allegro ma non troppo

Recorded July & November 2009, March 2010

London, BBC Maida Vale Studios & Air Studios (November 2009)

belohlavek_lewis_beethoven_complete_piano_concertos244402.rar – 628.5 MB

belohlavek_lewis_beethoven_complete_piano_concertos244403.rar – 359.8 MB

His complete set of the Beethoven sonatas enjoyed extraordinary acclaim in the UK, culminating in the prestigious ‘Recording of the Year’ award from Gramophone magazine for the fourth volume in 2008. Encouraged by what has now become a worldwide success, Paul Lewis has chosen to turn his attention to the five piano concertos with these distinguished partners. Recorded between July 2009 and March 2010, these interpretations paint a portrait of Beethoven full of light and shade.

Paul Lewis and Jirí Belohlávek have produced a set of the Beethoven piano concertos that puts them closer to their Classical-era roots while conveying a sense of excitement in Beethoven’s daring and innovative writing. This is not a boldly stated and theatrically dramatic reading of these works; one might say it’s conservative, but not so much so that the listener can’t help being moved by the rousing ending of the Emperor Concerto or caught up in the energy of the opening movement of the Concerto No. 3. Lewis gives the slow movements elegance and gracefulness with a touch that is wonderfully legato. Yet he knows how to change his articulation to help change the character and shape of each phrase throughout the concertos, adding interest to the music without overdoing any drama. He and Belohlávek work well together in this, neither one being indulgent, and with Belohlávek keeping the orchestral colors very much in line with the piano. Their interpretation sounds completely natural to Beethoven’s style, from the first to the last concerto. Harmonia Mundi’s sound is very clear and present, and equally balanced between the orchestra and piano. –Patsy Morita, AllMusic

With this three-disc album of Beethoven’s piano concertos Paul Lewis complements his earlier set of the 32 sonatas and also his appearances at the Proms this summer where for the first time all five concertos will be played by a single artist. So may I say at once that Harmonia Mundi’s eagerly awaited set is a superlative achievement and that Lewis’s partnership with Jirí Belohlávek is an ideal match of musical feeling, vigour and refinement.

True, for aficionados of eccentricity – even of brilliant eccentricity – from the likes of Gould, Pletnev and Mustonen, Lewis may at times seem overly restrained but the rewards of such civilised, musically responsible and vital playing seem to me infinite. Above all there is no sense of an artist looking over his shoulder to see what other pianists have come up with. Throughout the cycle Lewis is enviably and naturally true to his own distinctive lights, his unassuming but shining musicianship always paramount. His stylistic consistency can make the singling-out of this or that detail irrelevant, yet how could I fail to mention Lewis’s and Belohlávek’s true sense of the Allegro con brio in the First Concerto, in music-making that is vital but never driven? Less rugged than, say, Serkin, such playing is no less personal and committed. In the central Largo Lewis achieves a quiet, hauntingly sustained poise and eloquence, while in the finale his crisp articulation sends Beethoven’s early ebullience dancing into captivating life.

The same virtues characterise the Second Concerto; but when it comes to the Third, Lewis and Belohlávek (and one is always aware of a true partnership) hit a more controversial note. The first movement is less con brio than from most, as if to emphasise Beethoven’s step towards a darker region of the imagination (what EM Forster memorably called “Beethoven’s C minor of life”), while the finale is thought-provoking in its restraint. Yet once again Lewis’s comprehensive mastery is devoid of all overt display, and in the Fourth Concerto his playing achieves a rare nimbleness, affection and transparency. And if there are those who, again, wish for a higher degree of drama and assertion, others will recognise an artist who, in Charles Rosen’s words, achieves so much while appearing to do so little (pianists such as Lipatti, Solomon and Clara Haskil come to mind). At the same time the Fourth Concerto contains some delightful surprises. Lewis’s ad libitum flourish at 6’12” in the finale provides an exuberant touch, as do his deft and witty arpeggiations of the chords just before the concerto’s homecoming. Here in particular is an engaging and playful rejoinder to the Andante con moto’s introspection, the entire performance delectably animated and light-fingered. Nor is there a hint of strain or strenuous characterisation in the Fifth Concerto. Lewis’s first entry in the Adagio has a slight catch in the voice, as it were, to register the music’s sublimity, and his overall approach is devoid of the tub-thumping rhetoric familiar from too many Emperors.

And so, all in all, these records take their place among the finest Beethoven piano concerto performances so that even when you recall beloved issues by Wilhelm Kempff, Emil Gilels, Radu Lupu and Murray Perahia (to name but four), Lewis ensures that you return refreshed and with a renewed sense of Beethoven’s range and beauty. Personally I would never want to be without any of those previous discs, nor without Argerich’s never-to-be-completed recordings (sadly she considers the Fourth Concerto outside her scope; can her friends and musical partners Nelson Freire and Stephen Kovacevich persuade her otherwise?). Balance and sound are natural and exemplary, leaving us to look forward to Lewis’s forthcoming CD of the Diabelli Variations, for Brendel the greatest of all keyboard works. This is a cycle to live with and revisit. –Bryce Morrison, GramophonePaul Lewis is rightly considered one of the most gifted youngish pianists (he is 38) who devote themselves mainly to the central Viennese classical repertoire, and his set of the complete Beethoven sonatas is a fine achievement, though I’m sure he would be the first person to make criticisms of it.

This new set of the Beethoven concertos is interestingly different in emphasis, in that whereas I had previously thought of Lewis as primarily a thoughtful, searching player, in the mould of his mentor Alfred Brendel, these accounts score more strongly on extroversion, combativeness vis-à-vis the lively accompaniments of the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Jirí Blohlávek, and even mischief.

It is significant that Lewis chooses to play the most flamboyant and longest of the alternative cadenzas that Beethoven wrote – though that is nowhere indicated in the booklet. In the First Concerto, the third cadenza Beethoven wrote involves a rambling mass of scales, arpeggios and thumped chords lasting a full five minutes, which I don’t want to hear again. The first cadenza for the first movement of the Fourth is shorter, but still, in comparison with the rest of that sublime movement, an undisciplined rant.

As to the approach: take the slow movement of the Emperor, in which the hushed strings play a beautifully inward melody, and then the piano enters with its answering theme, pianissimo and espressivo.

Though Lewis is capable of carrying out both those instructions, here he gives us an only moderately quiet and not expressive account, hardly different from the forte passage in double thirds that follows.

That surprised me, but is in line with the general joie de vivre which characterises the whole cycle, and in which Belohlávek is fully complicit.

This is not as fully rounded an account of these inexhaustible works as several others, but it is full of life and energy. –Michael Tanner, BBC Music Magazine