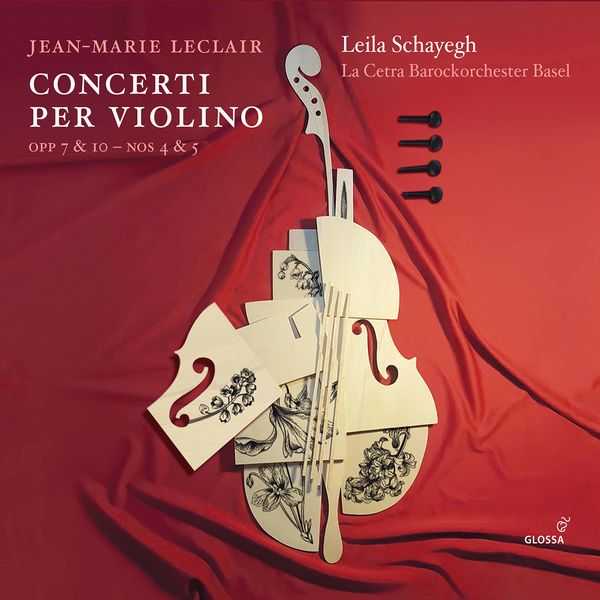

Composer: Jean-Marie Leclair

Performer: Leila Schayegh, La Cetra Barockorchester Basel

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: Glossa

Catalogue: GCD924206

Release: 2022

Size: 1.14 GB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: yes

Violin Concerto in E Minor, Op. 10 No. 5

01. I. Allegro ma poco

02. II. Largo

03. III. Allegro

Violin Concerto in F Major, Op. 10 No. 4

04. I. Allegro ma poco

05. II. Andante gratioso

06. III. Allegro

Violin Concerto in A Minor, Op. 7 No. 5

07. I. Vivace

08. II. Largo

09. III. Allegro assai

Violin Concerto in F Major, Op. 7 No. 4

10. I. Allegro

11. II. Adagio

12. III. Allegro

It’s almost impossible not to be fascinated by the life and music of Jean-Marie Leclair (1697-1764), such are its colourful contradictions. A career that began as a dancer but which ultimately saw him become one of France’s greatest violinist-composers, famed for not only for his breathtakingly virtuosic technique but also for the exquisite sweetness and good taste of his playing – hence the much-documented 1739 concert showdown in Amsterdam between him and the Italian virtuoso Locatelli, declared a draw after Locatelli played like the devil and Leclair like an angel. Then in the 1740s his abandonment of the violin for an unsuccessful career as an opera composer, followed in time by a move to lodgings in one of Paris’s dodgier areas, and finally being stabbed to death outside his own front door in a murder case that has never been solved.

For this concertos programme, warmly recorded in Basel’s Martinskirche, Leila Schayegh and La Cetra Barockorchester Basel have chosen numbers 4 and 5 from each of Leclair’s two sets of violin concertos, the Op. 7 first of which dates from that aforementioned Amsterdam adventure, and the Op. 10 second from the early 1740s. The first thing worth pointing out is the project’s period-instrument decisions, because the ensemble strings are using the lighter baroque bows with clipped-in frogs (rather than screw-type), and also gut strings – because although silver-wound gut appeared in the 1700s, even by the 1740s it would still have been prohibitively expensive for most musicians. Plus, they’re tuned at A=408 Hz, i.e. even lower than the Baroque standard of 415 Hz. This goal here has been to reflect the variety of pitch in France at the time, which could range from as low as 390 Hz to above today’s standard 440 Hz. Also to create a darker, slightly rougher orchestral sound onto which the solo violins with their screw-type bows – Schayegh as principal soloist and Christoph Rudolf on second – can provide subtle colouristic and timbral contrast. And all of that has been achieved, because there’s a gorgeously soft, velvety darkness to the overall ensemble sound, while equally being incredibly light of tread, while the soloists are sounding especially sweet and bright on top.

The pleasure continues with the musicians’ palpable awareness of Leclair’s dance roots and overall elegance. Rhythms are crisp and springing, articulation unfailingly neat, and when Leclair was known for disliking runaway speeds, the tempi here are all correspondingly dignified, typified by the steady grace Op. 10 No. 5 in E minor’s concluding Allegro. “Grace” is likewise the operative word for all the solo work. Just listen to the sweet-voiced, easy legato lyricism with which Schayegh meets the succession of virtuoso techniques thrown at her in the impishly sunny major-keyed section of Op. 7 No. 5’s concluding Allegro assai; or, to return to Op. 10 No. 5, her endless double-stops, bariolage and leaps in its opening Allegro ma poco. Perhaps the greatest achievement, though, is the fact that all of this neatly articulated tastefulness has, from one and all, been achieved without for one single second sounding bland or coolly academic. Instead, it verily brims with life, colour and joy.