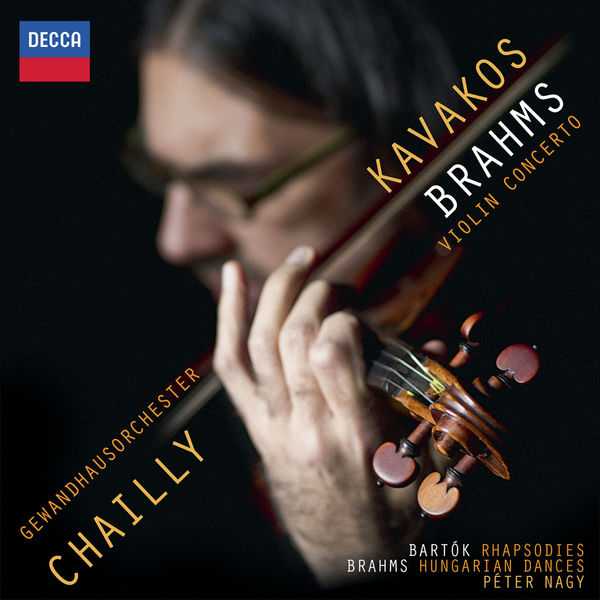

Composer: Béla Bartók, Johannes Brahms

Performer: Leonidas Kavakos, Peter Nagy

Orchestra: Gewandhausorchester Leipzig

Conductor: Riccardo Chailly

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: Decca

Catalogue: 4786197

Release: 2013

Size: 1.36 GB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: yes

Brahms: Violin Concerto in D, Op. 77

01. 1. Allegro non troppo

02. 2. Adagio

03. 3. Allegro giocoso, ma non troppo vivace – Poco più presto

Bartók: Rhapsody No. 1 for Violin and Piano, BB 94a (Sz.87)

04. 1. Moderato (Lassú)

05. 2. Allegretto moderato (Friss)

Bartók: Rhapsody No. 2 for Violin and Piano, BB 96 (Sz.89) (1928, rev.1944)

06. 1. Moderato (Lassú)

07. 2. Allegretto moderato (Friss)

08. Brahms: Hungarian Dance No. 1 In G Minor

09. Brahms: Hungarian Dance No. 2 In D Minor

10. Brahms: Hungarian Dance No. 6 in B Flat

11. Brahms: Hungarian Dance No. 11 In D Minor

Bartók: Roumanian Folk Dances, Sz. 56, BB 68

12. I. Jocul cu Bâtǎ

13. II. Brâul

14. III. Pe Loc

15. IV. Buciumeana

16. V. “Poarga” Româneascǎ

17. VI. Mǎnuntelul 1, Mǎnuntelul 2

it demonstrates not only the wonderful poise and instinctive elegance of Kavakos’s playing…but also the transparency that is such a characteristic of Chailly’s Brahms with this orchestra…It’s a long time since there was a new version of this concerto as good as this

With his long hair and wild yet intellectual look, it’s easy to see Greek violinist Leonidas Kavakos resembles Joseph Joachim, the dedicatee and premiere-giver of Johannes Brahms’ Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 77. It’s often been said that the Brahms work is not “for the violin” but “against the violin,” and indeed its fascination resides in the way it bends the language of virtuoso display to Brahms’ own compositional demands. It takes a superb talent to not only get through the notes but dominate the performance, and Kavakos does it. In the first movement he has a nifty way of dictating the transitions from the violin, and the numerous double stops and huge arpeggios with which the violin seems to try to escape the harmonic structure of the movement are invariably executed with élan. The finale sparkles with southern Europen vigor, and the venerable Gewandhaus Orchestra of Leipzig seems positively enlivened by the proceedings under the baton of Riccardo Chailly. If there’s a complaint here, it’s that the rest of the program does not live up to the Brahms concerto. The two Bartók Rhapsodies for violin and piano fit well enough with the four Brahms Hungarian Dances, in recital arrangements by Joachim himself, but not so well with the Brahms; the program seems to lurch from orchestral to chamber music, and from the Gewandhaus to the Berlin studio where the chamber pieces were recorded. For the Brahms concerto itself, however, the album is worth the money: the work would have filled an entire LP back in the day, and indeed Kavakos’ commanding performance is reminiscent of some of the classics of that era.