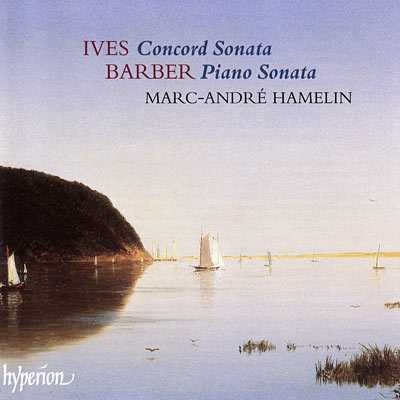

Performer: Marc-André Hamelin

Composer: Samuel Barber, Charles Ives

Audio CD

SPARS Code: DDD

Number of Discs: 1

Format: FLAC (tracks+cue)

Label: Hyperion

Size: 176 MB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: yes

# Sonata No. 2: Concord, Mass., 1840-60, for piano (& optional viola, flute), S. 88 (K. 3A2)

Composed by Charles Ives

with Jaime Martin, Marc-Andre Hamelin

# Sonata for piano, Op. 26

Composed by Samuel Barber

with Marc-Andre Hamelin

01. Emerson: Slowly

02. Hawthorne: Very Fast

03. The Alcotts

04. Thoreau: Starting Slowly And Quietly

05. Allegro Energico

06. Allegro Vivace E Leggiero

07. Adagio Mesto

08. Fuga: Allegro Con Spirito

An Embarrassment of Riches

This CD contains probably the two greatest piano sonatas composed by Americans. Some might disagree, but few will disagree that they are great, if not at the very top of any list. [See below for comments about the Barber Sonata; most of this review will be about the Ives.] As to the Ives, frankly, I agree with Lawrence Gilman’s reaction when he heard the première by John Kirkpatrick of the ‘Concord’ Sonata in 1938: ‘This sonata is exceptionally great music–it is, indeed, the greatest music composed by an American, and the most deeply and essentially American in impulse and implication.’ I can think of no other American music that stirs me as deeply as this. And, mirabile dictu, we have had three wonderful new recordings of it in the past year, corresponding roughly with the fiftieth anniversary of Charles Ives’s death in 1954. The three pianists are magnificent: Pierre-Laurent Aimard, Steven Mayer and, on this disc, Marc-André Hamelin. I’ve reviewed the Mayer here at Amazon. I had nothing to add to the raves by Amazon customer reviewers about the Aimard and so I didn’t review it, but I count it among the best recordings of the year. And then there is this newly issued recording by Hamelin. He recorded it once before, in 1988, and although this performance is similar in many respects, one can feel that he is at greater ease with it than sixteen years ago. Both performances are wonderful, but this one is, as I said to a friend recently, ‘a corker.’

I am not an Ives scholar, like fellow Amazon reviewer Bob Zeidler, and I hope that he will be adding his review to this page some time soon. But I do have a few thoughts about this recording, and some brief comparisons with the two other recent issues by Aimard and Mayer. As I said in my Mayer review, the easiest course is simply to buy all three, but I recognize that might not be the choice than many will make. So, how does one make a choice about which version to buy? Well, first of all there is the question of price: Mayer’s is on the budget Naxos label; the other two are at full price. Couplings might make a difference to some. Aimard’s includes Susan Graham singing seventeen of Ives’s songs accompanied by Aimard; they are simply smashing. Mayer’s includes other shorter piano works: ‘Varied Air and Variations,’ ‘The Celestial Railroad,’ and Transcription No. 1 from ‘Emerson.’ Also, the four movements of the ‘Concord’ Sonata are separately introduced by actor Kerry Shale reading appropriate passages from Ives’s ‘Essays Before a Sonata.’ (The Essays are the length of a short book and can be accessed online at Project Gutenberg for the interested among you. I take pride in having proofread the ‘Essays’ for Project Gutenberg. If you catch some typos, they’re mine!) Hamelin’s CD, of course, is coupled with the Barber Sonata.

How do the performances differ? Well, for starters, Aimard includes the optional tiny viola part at the end of the ‘Emerson’ movement (played by viola superstar, Tabea Zimmermann) and the flute part in ‘Thoreau’ (played by flute superstar Emanuel Pahud). Nice as this is, it is not a deal-maker or -breaker. I cannot vouch for the fact that all three pianists play precisely the same version of the ‘Concord.’ I didn’t catch any differences but there may be some because there are as many different versions of the sonata as there are leaves on a tree–Ives kept making changes. I believe, though, that all three primarily are using the version Ives made in the late 1940s. Movement timings might be instructive: Hamelin’s traversal is by far the fastest at 42’54”; Aimard’s is 48’16”, Mayer’s roughtly 52′, not counting Shale’s readings in between movements. Hamelin’s ‘Emerson’ is almost a full three minutes faster than Mayer’s. And his version of the ferociously difficult ‘Hawthorne’ is a full two minutes faster than either of the other versions. Further, Hamelin’s inflections seem more finely nuanced, even at the greater speed. Still, his approach seems almost romantic at times, especially as compared to Mayer’s which seems more, for lack of a better word, ‘modern.’ Aimard’s (and perhaps I’m thinking this simply because of his long association with Messiaen and his music) seems more impressionistic. The sonata contains a great deal of layering and blurring of textures and all three pianists manage that extremely well. Where Mayer and Hamelin seem to have an edge is in the sharp ‘American’ outlines of the quicker rhythms. I particularly like what they do with the march rhythms (e.g. when ‘Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean’ is quoted) and the proto-jazz sections (although, to be honest, Aimard gets in some licks, too).

The more I think about it, the more I realize I get something from each version and and I wouldn’t want to be without any of them. I guess my initial impulse to say ‘Buy all three’ was stronger than I realized. Buy all three!!

Finally, I must say that the performance of the Barber Sonata is the most vital I’ve ever heard. Not only is the popular final movement, the Fugue, played with point and almost inhuman aplomb, but the powerful, dissonant first movement, the almost Mendelssohnian (well, light-textured anyhow) second movement, and the lovely adagio are exceedingly convincing.

An extraordinary release. I’d hate to be the folks who have to give out prizes for best piano performance or best CD of twentieth-century music for 2004. Maybe they could award a tie!

Hamelin, yes. I wonder, since his dear singing of Reger’s Telemann Variations, why not do the same of the Concerto? Sort of ugly in it self, that hunchback and club foot hold a golden heart between them, and Hamelin did not lift its cloak. One might well argue that nothing was done there on purpose, leaving the lifting-recognizing to the cloak’s real owner – us, that is – but to such effect he could have not played at all. I hope to hear him sing again, the Ives’ Concord. Thank you.

Oh dear, Bach that is, not Telemann.