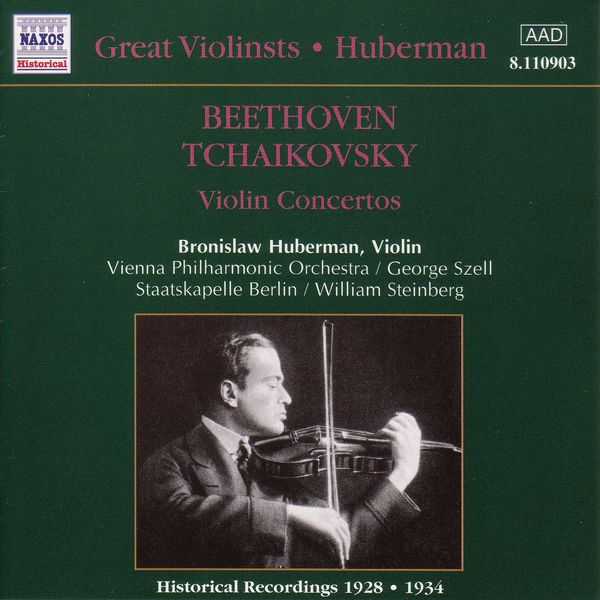

Composer: Ludwig van Beethoven, Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky

Performer: Bronisław Huberman

Orchestra: Wiener Philharmoniker, Berlin Staatskapelle

Conductor: George Szell, William Steinberg

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: Naxos

Catalogue: 8110903

Release: 2000

Size: 212 MB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: yes

Beethoven: Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61

01. I. Allegro ma non troppo

02. II. Larghetto

03. III. Rondo: Allegro

Tchaikovsky: Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 35

04. I. Allegro moderato

05. II. Canzonetta: Andante

06. III. Finale: Allegro vivacissimo

Virtuoso violinist Bronislaw Huberman was an idealist, an ardent Pan-European and cofounder (with William Steinberg) of the Israel Philharmonic. He was, in a sense, the prototype for such present-day fiddling mavericks as Kremer, Zehetmair, Tetzlaff and Kennedy. Huberman’s open letter to the conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler, in which he pledged support of the persecuted, and refused to perform in Nazi Germany, has become famous, and his astringent though frequently dazzling playing translates that steely resolve into musical terms.

This Naxos coupling is very nearly the answer to a prayer. Huberman’s interpretation is more in line with, say, Zehetmair and Brüggen than the stately readings of Kreisler, Szigeti, Menuhin or David Oistrakh. His lively speeds and darting inflections spin silver beams where others opt for (for some misplaced) ‘Olympian’ heights. The luminosity of the reading, its radiance and refusal to dawdle, run counter to the languid sweetness favoured by various of his peers and successors.

The 1929 Tchaikovsky recording is peerless.

Huberman’s first entry reveals all: elastic phrasing, sweeping portamentos and generous rubato stamp a giant personality. Thereafter, quicksilver bowing and a steely spiccato level with the best of the period. Brahms loved Huberman’s playing (he promised the budding youngster a Fantasy but never lived to compose it), and no wonder, given the veiled beauty of his tone (Canzonetta) and the uninhibited swagger of his bravura style (finale).

You simply have to hear Huberman’s recording, and Naxos’s give-away price makes it a mandatory purchase. However, the transfer of the Beethoven, although perfectly adequate, is rather spoiled by excessive digital noise reduction.

On one occasion in the first movement, the violinist momentarily disappears; in the second movement two chords inadvertently become one. But these technical reservations will likely prove trifling for anyone who has never heard Huberman before. There are no greater violin recordings in existence.