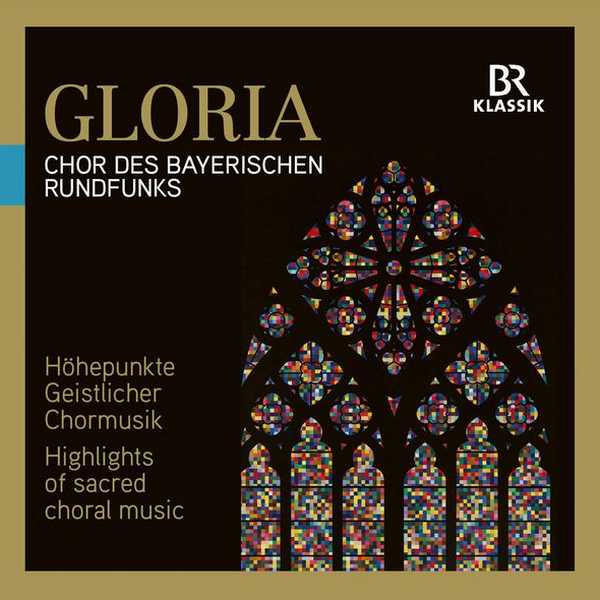

Performer: Chor des Bayerischen Rundfunks

Orchestra: Concerto Köln, Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks

Conductor: Peter Dijkstra, Mariss Jansons, Bernard Haitink

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: BR Klassik

Catalogue: 900518

Release: 2017

Size: 351 MB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: yes

01. Bach: Mass in B Minor, BWV 232: Gloria in excelsis Deo

02. Gounod: Messe solennelle de Sainte Cécile, CG 56: Kyrie

03. Schubert: Mass No. 2 in G major, D167: Gloria: Gloria in excelsis Deo

04. Dvořák: Stabat Mater, Op. 58, B. 71: Eia, mater

05. Beethoven: Missa Solemnis in D major, Op. 123, “Missa Solemnis”: Kyrie: Kyrie eleison

06. Handel: Dixit Dominus, HWV 232: Dixit Dominus Domino meo

07. Bach: Magnificat in D major, BWV243: Gloria Patri

08. Bach: St Matthew Passion, BWV244, Part III: Chorale: O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden

09. Bach: St John Passion, BWV245, Part I: Chorale: Herr, unser Herrscher

10. Haydn: Die Schopfung (The Creation), Hob.XXI:2: Part I: Die Himmel erzahlen die Ehre Gottes (The heavens are telling the glory of God)

11. Verdi: Messa da Requiem: Dies irae: Dies irae, dies illa

12. Kodály: Missa brevis: Gloria

13. Pärt: Berliner Messe: Credo

14. Bach: Christmas Oratorio, BWV248, Part I: Jauchzet, frohlocket, auf, preiset die Tage

15. Handel: Messiahh, HWV 56, Part II: Hallelujah

“Chorus”, the name for a community of singers that evolved in Europe from the Middle Ages onwards, derived from the choros of Ancient Greek theatre. The first polyphony soon arose from the initially purely monophonic Latin church music, sung since Late Antiquity and collected and standardised under Pope Gregory I as Gregorian chant. The Renaissance then brought forth complex types of polyphonic a cappella works; these reached new heights during the course of the 16th century in multiple choirs, bringing new experiences in sound through the juxtaposition – whenever space allowed – of several choirs inside churches. The choir became increasingly functional – above all in operas, cantatas and oratorios. By the Late Baroque period, the development stage had been reached that still characterises today’s concept of the choir: a fixed choral ensemble, clearly differentiated from an instrumental one (the orchestra); works of primarily spiritual content; texts in Latin but, increasingly, in national languages as well; and everything gradually becoming more representational in character. The first bourgeois choral societies of the 19th century – the forerunners of today’s philharmonic choirs – were ensembles of a size that could compete as well as cooperate with symphonic orchestras. In choral singing, the content – sacred and secular, nationalist and idealist, reactionary and revolutionary – could be expressed with powerful emotion, not only in separate compositions but also in choral numbers extracted from their former, broader contexts. As the 19th century progressed, combinations of popular pieces appeared that were seldom coherent in terms of their content but still sounded highly impressive (in a musical context this is not referred to as an anthology but more usually as a Florilegium), and it is these that still determine today’s concert programmes.

The Chor des Bayerischen Rundfunks can be heard here performing highlights of sacred choral music dating from the Baroque period to modern times. Even today, three hundred years later, the large oratorio choirs by Bach and Handel are as vivid, realistic and captivating as ever. Haydn succeeded in preserving this for the sacred music of the Wiener Klassik era, which reached its peak in Beethoven’s Missa solemnis. The heartfelt masses composed by Schubert are typical of early German Romanticism, Gounod’s St. Cecilia Mass is the French equivalent here, and Dvořák’s Stabat mater represents Bohemian Romanticism of the mid- to late 19th century. Verdi’s famous Messa da Requiem testifies to the close relationship between Italian opera and Italian church music. The Mass written just before the end of World War II by the Hungarian composer Kodály is still Late Romantic in its musical language, while in his Berlin Mass, written shortly before the start of the 20th century, the Estonian composer Arvo Pärt maintains the Tintinnabuli style that informs and inspires his work.