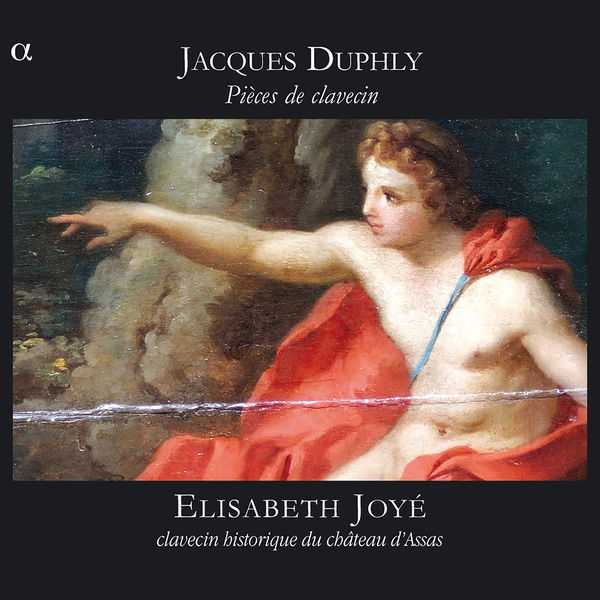

Composer: Jacques Duphly

Performer: Elisabeth Joyé

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: Alpha

Catalogue: ALPHA150

Release: 2009

Size: 484 MB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: cover

01. La Forqueray, Rondeau

02. Médée, Vivement et fort

03. Allemande en Do

04. Courante La Boucon

05. Rondeaux

06. La Millettina

07. La Pothoüin, Rondeau, Modérément

08. Chaconne

09. Allemande en Ré

10. Courante

11. La Vanlo

12. Les Grâces, Tendrement

13. La De Belombre, Vivement

14. La Félix, Noblement

Jacques Duphly published four harpsichord collections (1744-68), modelled chiefly on those of Rameau. Book 3 includes a sombre rondeau in bass-viol range called ‘La Forqueray’ after the late virtuoso of that instrument, a brilliant chaconne of 285 bars, and a savage tirade entitled ‘La Médée’. Book 4 contains the enchanting rondeau, ‘La Pothouin’. D’Aquin wrote that ‘in general his pieces are sweet and amiable: they take after their father’. Born in 1715, the year of Louis XIV’s death, he died on July 15, 1789, the day after the storming of the Bastille, in an apartment in the Hôtel de Juigné, lonely, forgotten and without a harpsichord.

Jacques Duphly was — like English composer Charles Avison — among the last of his stylistic line, a French harpsichordist whose lifespan reached up to one day beyond the storming of the Bastille. Duphly’s choice of instrument and approach in composing for it continued — and apparently concluded — a tradition that stretched back to the early seventeenth century and included among its proponents such figures as François Couperin and Jean-Philippe Rameau. Blindfolded, listeners would have a hard time telling certain works of Duphly apart from Couperin, although by comparison they are longer; Couperin’s pieces average about 4-6 minutes, whereas with Duphly it’s more like 6-8 minutes. It isn’t just a matter of pacing or repeats; Duphly’s sequences are longer, as are his harmonic projections of a given tune. Duphly published four volumes of harpsichord music and only the last one, published in 1768, shows some concessions to classical style; the rest are resolutely Baroque and show no evidence of yielding any quarter to the milieu of that upstart, the piano. Recordings of Duphly within his own context, rather than a piece or two offered within a collection or to fill out a disc of Couperin, are reasonably uncommon, although a recording of his complete output, on four discs, was made back in the 1990s. Alpha Productions’ Jacques Duphly: Pièces de Clavecin, featuring harpsichordist Elisabeth Joyé, is a very good introduction to his general sound and far more accessible by virtue of its selectiveness, compiling 14 of the best of Duphly’s 52 surviving compositions.

One of the best things about being the last of a line is that one is able to investigate a given style and tradition to the nth degree and Duphly seems happy to do so within the Baroque harpsichord medium with little or no recourse to outside influences. La Forqueray is one of the deepest and most fully developed character pieces in all of French harpsichord literature; the Rondeaux from Duphly’s First Book takes an idea similar to one that drove Couperin’s familiar Les Baricades mistérieuses and develops it with far more variety, although one might argue that the slightly monotonous tone of Les Baricades is part of its appeal. Joyé plays a mid-eighteenth century harpsichord housed at the Chateau d’Assas in Southern France once beloved of legendary harpsichordist Scott Ross; the front cover of the CD represents a detail from the painting inside its case. It has a lovely, full, organic sound that suits Duphly’s music well, and Alpha Productions’ recording is quite sympathetic and Joyé’s interpretation is splendid in most respects. The only quibble is that once in awhile Joyé employs some measure of rubato that makes one wonder if Duphly, given his artistic lineage, favored such expressive devices; also in La Milletina there are a number of repeated figures that commonly would be given first as “forte” and the second time as “piano,” whereas Joyé plays the whole piece forte. Exactly what Pierre-Louis d’Aquin de Château-Lyon meant when he reported (in the 1750s) “[Duphly] has a very light touch and a certain gentleness” is something that we cannot know now, and the early prints of Duphly provide barely more than the notes in these pieces, so no harm, no foul vis à vis Joyé’s interpretive acumen.