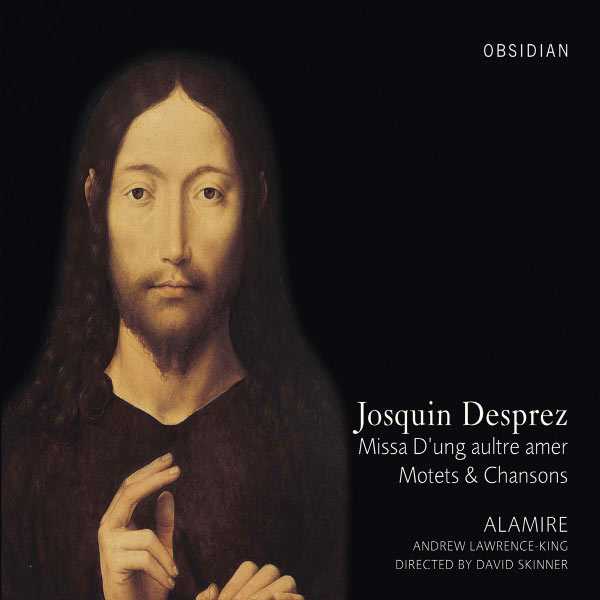

Composer: Josquin Despres, Johannes Ockeghem

Performer: Alamire, Clare Wilkinson, Andrew Lawrence-King

Conductor: David Skinner

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: Obsidian

Catalogue: CCLCD701

Release: 2007

Size: 262 MB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: cover

01. Ockeghem: D’un autre amer

Josquin: Sanctus “D’ung aultre amer”

02. Kyrie

03. Gloria

04. Credo

05. Sanctus – Tu solus qui facis mirabilia

06. Agnus dei

07. Josquin: De tous biens plaine

08. Josquin: Mille Regretz

09. Josquin: Ave Maria … Virgo serena

10. Josquin: Fortuna d’un gran tempo

11. Josquin: Planxit autem David

12. Josquin: Cela sans plus

13. Josquin: Qui belles amours

14. Josquin: Sanctus “D’ung aultre amer”

15. Josquin: Tu lumen, tu splendor patris

16. Josquin: La Bernardina

17. Josquin: Victimae paschali laudes / D’ung aultre amer

18. Josquin: Adieu mes amours

19. Josquin: Ile fantazies de Joskin

20. Josquin: Tu solus qui facis mirabilia

Josquin’s music, much of which is both difficult and remote in time and place, often attracts performers who try to clarify a certain aspect of it. Yet some of his music — the chanson Mille regretz (A thousand regrets), for example — are not difficult at all and speak a basic emotional language clearly across the centuries. This was Josquin’s genius: in the words of theorist Glareanus, quoted in the booklet here, “there was nothing in this field that he could not do.” The booklet essay by conductor and Cambridge University professor David Skinner entertainingly introduces Josquin and the problems surrounding his oeuvre for general listeners. There are some terrific anecdotes gleaned from recent scholarship. Luther’s famous remark that “Josquin is the master of the notes . . . while other composer must do as the notes dictate” is here, but even better is a story touching on Josquin’s popularity in his own time, and especially after his death: one nobleman commented that now that Josquin was dead, he was putting out even more works than he had when he was alive. Skinner and his all-adult octet Alamire set out not to put Josquin into deep context, but to convey his breadth; secondarily, they perform mostly early pieces and try to examine the formation of his style. The Missa D’ung aultre amer, based on a chanson by Ockeghem, is not necessarily the centerpiece of the program but an example of Josquin’s early mass style, and it works well for the listener trying to get a grip on the masses: its contrapuntal artifice, while ingenious, is not buried in this music and is fully audible in the measured, clear performances by Alamire. The work also serves to illustrate Josquin’s desire to outdo himself by returning to material he had previously treated; two other works take up the D’ung aultre amer music in different ways. After the mass come motets performed by Alamire, along with chansons sung by Clare Wilkinson to the accompaniment of Andrew Lawrence-King’s Renaissance harp, and pieces (either vocal or instrumental originally) played by Lawrence-King alone. Needless to say, this is not a program that would have been heard in an Italian noble establishment in Josquin’s time. The lurch from the massive motet Planxit autem David to the little harp rendition of the chanson Cela sans plus is something like what you would experience if a pianist took the stage after a Beethoven symphony to perform Rage over a Lost Penny. Nevertheless, the performances are well suited to the music; Wilkinson’s limpid readings of the chansons performed vocally are lovely (one wishes there were a few more of these); it’s hard to think of another Josquin disc that captures his breadth in quite this way. Recommended as a building block for a library of Josquin’s music.