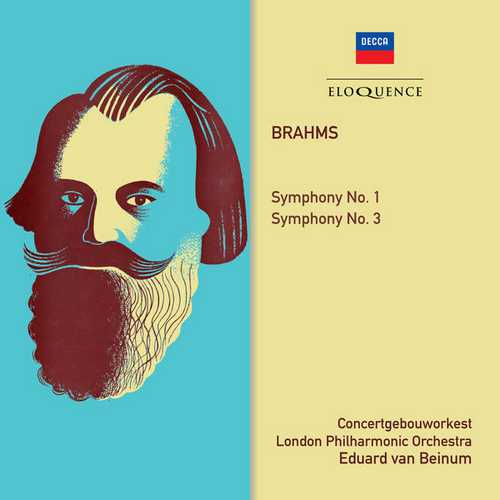

Composer: Johannes Brahms

Orchestra: Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, London Philharmonic Orchestra

Conductor: Eduard van Beinum

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: Eloquence

Catalogue: ELQ4825499

Release: 2018

Size: 224 MB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: cover

Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68

01. 1. Un poco sostenuto – Allegro – Meno allegro

02. 2. Andante sostenuto

03. 3. Un poco allegretto e grazioso

04. 4. Adagio – Piu andante – Allegro non troppo, ma con brio – Piu allegro

Symphony No. 3 in F major, Op. 90

05. 1. Allegro con brio – Un poco sostenuto – Tempo I

06. 2. Andante

07. 3. Poco allegretto

08. 4. Allegro

Eduard van Beinum made three recordings of Brahms’s First Symphony, all with the Concertgebouw Orchestra of which he had become principal conductor after World War II. This newly remastered Eloquence album presents his second thoughts on the symphony, as it were, from September 1951. Cut from the same cloth as his Beethoven symphonies, Van Beinum’s interpretation is notable for its dignified, classical approach.

There are two Van Beinum studio accounts of the Third Symphony: dating from 1946, this is the first of them, made by Decca in the conductor’s first sessions with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, just two months after his impromptu concert debut with them: substituting at the last minute for Albert Coates, Van Beinum happened to be on business in London, but he did not have his tails with him and conducted the concert dressed in a brown suit. In the hands of Van Beinum, the Third is treated not as an emotional roller-coaster, but as a powerful and finely crafted statement of Brahms’s respect for the composers who preceded him, not least Robert Schumann: in the symphony’s first movement, Brahms pays poignant tribute to the memory of the man who had nurtured his career at its outset by quoting from the latter’s ‘Rhenish’ Third Symphony.

Van Beinum expressed approval of the LPO’s autonomy of organisation and spirit: ‘this means that the members of the orchestra will, so to speak, be rapping each other over the knuckles if necessary. They feel responsible, which is very important’. The respect was evidently mutual, because the conductor was soon invited back for regular concerts, and indeed Decca recordings, and in 1949 he became the LPO’s chief conductor. The technical discipline and idiomatic flow of this Brahms Third pays its own testimony to the quickly achieved rapport between conductor and orchestra, later recalled by a former LPO violist: ‘Firstly, he won the full trust and cooperation of the players. This he did through his musical authority and his human understanding. To him, the musicians he worked with were not anonymous employees of a musical organisation, but artists who more or less shared his own tastes and standards’.

‘There is a good sense of the concert hall about the Van Beinum recording; not the feeling of a confined studio. The colour is clear, and the range of tone is wide … throughout one notices how clearly the inner parts come through which is good testimony to conductor and engineers alike. The third and fourth movements show the performers at their best.’ Gramophone, December 1946 (Symphony No.3)

‘Van Beinum keeps his No. 1 suitably impressive without being portentous … [he] achieves liveliness of effects by his magnificent drive; his breadth of phrasing does not hamper forward movement … The individual colouring of the instruments is notably clear and attractive.’ Gramophone, June 1952 (Symphony No.1)