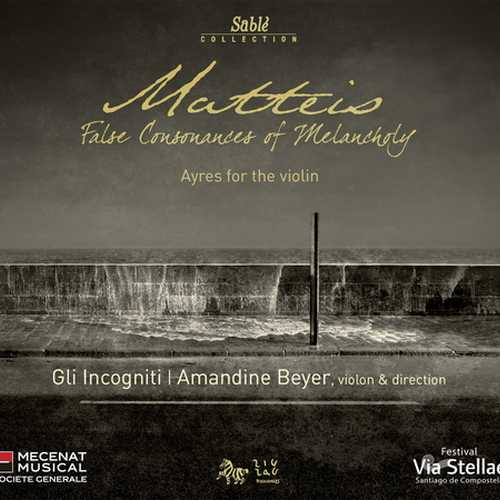

Composer: Nicola Matteis

Performer: Gli Incogniti

Conductor: Amandine Beyer

Number of Discs: 1

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: Linn

Release: 2009

Size: 1.33 GB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: yes

01. Sonata (Adagio)

02. Diverse bizzarrie Sopra la Vecchia Sarabanda o pur Ciaccona

03. Passaggio rotto. Andamento Veloce

04. Fantasia

05. Preludio in fantasia

06. Allegro

07. Aria malinconica (Adagio)

08. Giga (Allegro)

09. Aria Amorosa

10. Aria

11. Preludio

12. Musica (Grave-Presto)

13. Sarabanda (Adagio)

14. Aria

15. Aria burlesca (Presto)

16. Fuga (Prestissimo)

17. Giga. Al Genio Turchesco

18. Preludio

19. Adagio

20. Allemanda ad imitatione d’un tartaglia

21. Movimento incognito

22. Sarabanda Amorosa (Adagio)

23. Gavotta (Presto)

24. Preludio. Presto

25. Pavana Armoniosa

26. Il Russignolo

27. Preludio Allegro (Prestissimo). Malinconico (Adagio)

28. Aria (Adagio-Presto)

29. Vivace. Eco

30. Fuga (Presto)

31. Preludio (Adagio)

32. Prestissimo

33. Un poco di maniera Italiana. Aria Ridicola (Presto)

34. Aria

35. Fantasia

36. Preludio in ostinatione. Passagio rotto

37. Andamento malinconico. Divisone ad libitum

38. Grave. (Adagio)

39. Aria for the Flute

40. Giga

I have no idea why this album is named “False Consonances of Melancholy.” The celebrated violinist Nicola Matteis (c. 1650–c. 1700) published a treatise on continuo playing for the guitar entitled The False Consonances of Musick , but it has no bearing upon his four volumes of music, Ayres for the Read more , produced to considerable success between 1676 and 1685. Nor is there any especial emphasis on melancholy in the 40 short works included on this CD. Instead, we find a fanciful mix of dance forms, free-ranging preludes, and character pieces, with a broad expressive range. They include simple diatonic works and highly chromatic ones, sometimes flavored with sharp dissonances, such as occur when approaching cadences in major key pieces from the minor third.

The Baroque age wasn’t noted for pedantic precision in the use of language, but the titles of many selections by Matteis bear little or no resemblance to their content. The album offers up three gigues, one of them an irresistible tarantella in all but meter. One aria is actually a pizzicato Neapolitan serenade; another is a nascent minuet. A third finally is what we might think of as a slow, unusually beautiful aria from some unnamed Italian Baroque opera; while the thematic and harmonic cast of a seductive Sarabanda amorosa displays similar models as those that impressed a young Handel. A Ground on the Scottish Humor is as Celtic as lasagna, and filled with technically challenging variations that must have brought the house down when Matteis played it. (The prefaces to his volumes elaborate upon such matters as ornaments, tempo, and bowing.) Was it perhaps the proudly strutting aspect of the brilliant solo part that led the composer violinist to invoke a Scots stereotype?

As for Amandine Beyer, she first studied at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique de Paris before moving to Basel and entering the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis. Her master’s dissertation was on Stockhausen, but she’s since concentrated much of her professional time working as a member of various Baroque ensembles. Beyer has taken part in roughly 30 albums, though the six spotlighting her work as soloist for Zig-Zag Territories are among the most recent. She possesses enormous energy that, coupled with precise articulation, gives the faster movements on this record a rare brio. In slower pieces, such as the various preludes—and they really are allowed to be slow, rather than rushed through nervously—she employs a discrete vibrato to good effect, adding just enough brightness to her narrow but attractive tone. (Beyer’s own part of the liner notes mentions her placing the violin down around her lower ribs, citing descriptions of Matteis’s concerts soon after arriving in London. I don’t notice any difference to the sound compared to her other Baroque albums, and her full page publicity accompanying this release still shows her instrument under her chin; so who knows?) This is stylish playing of a high order. That can be said as well of her group, Gli Incogniti—a gambist, harpsichordist, and two guitar and theorbo specialists—who provide continuo of varying complexity, occasionally (as in a single fugue) rising to the level of equal participants.

With such zestful playing in music of great immediacy, can you expect otherwise than a strong recommendation?

FANFARE: Barry Brenesal

So, where does the curious title come from and who was Nicola Matteis? There is some confusion over when exactly he was born or died but he probably came from Naples and arrived in London in about 1672. There he made a great reputation as a violinist and composer with several publications. John Evelyn heard him play in November 1674 and so Matteis probably knew and is said to have influenced Henry Purcell. He purchased a property in Norfolk in 1714 and died in obscurity.

Matteis has been recorded before, for example by Nicholas McGegan and the Arcadian Academy on Harmonia Mundi (907067). Of his publications there are various ones entitled ‘Ayres for the Violin’ – at least four. One is called ‘False Consonances’ from 1682 and although these consist of separate movements with individual titles they can be formed as happens here into suites. Some of these suites comprise four movements others six or seven but each is normally headed with an improvisatory Prelude. On this recording the movements follow on quickly but there is a respectful gap between suites. Apparently Matteis when playing in public “simply”, according to Roger North, “selected movements from here and there”. But what about the title?

A False Consonance is really a poetic term for what the medieval church considered to be ‘the Devil’s interval’ – that is the augmented fourth or diminished fifth. What does that mean? It is the distance between say a C to an F sharp-three whole tones higher. It is hence also known as a tri-tone – in other words an awkward, ugly or uncomfortable melodic interval that should, by the laws of Palestrinan harmony be avoided. By the baroque period these laws and rules were often relaxed. In the first of two booklet essays Olivier Fourés reminds us from a contemporary treatise that “Any rule, however necessary it may be, is there to be broken”. It seems that Matteis’s character was a little wild and reckless. “He could not bear ill-timed applause” (please note proms audiences!) and improvised his programme as the mood took him”. He was also “a very prickly character” and this comes through the music often in its titles such as ‘Bizzerie all’Umor scozzese (A pretty hard Ground after the Scotch Humour to make a hand). Then there’s ‘Fuga curta per scarsezza di carta (A fugue, short through lack of paper) and several others. So, initially at least, Matteis is revealed as a curious and quixotic musician with a lively imagination for titles. He was a brilliant improviser and one who could sell himself if not his personality. After all this hype where does all of this leave the music heard on this disc?

Well I must report a little disappointment. I found only sporadic moments of special brilliance and although several melodies are long, arching and beautiful, none were memorable. In the second essay Amandine Beyer makes out a strong case for Matteis’s genius which does seem to be somewhat inflated. She also comments on how, physically, the music should be played. I quote “Many descriptions have been preserved of the violinist’s playing style … where he apparently held his instrument very low (around the level of the lower ribs) as seen in 17 th Century paintings and which is surely close to folk practice.” There are she says “no insoluble problems” except that is the “female physiology”. Perhaps this is the reason why, in the only, (slightly revealing) picture of Amandine Beyer on the cardboard casing she is holding the instrument quite normally.

What about musical highlights? Beyer is accompanied by a crack team of continuo players: sometimes a gamba with a baroque guitar or occasionally a theorbo and a harpsichord – or clavecin as the booklet insists on calling it. The players are thoughtful enough to hold back sensitively when the violin is especially busy and imaginative enough to come to the fore in the less interesting passages.

With a disc of forty tracks choosing highlights is not easy. But to give you a good taste you could start with the Sonata which makes up track 1. The continuo is quite active under the slow pulse filling out with scales, arpeggiated chords and passing notes. The next track is a sort of Chaconne with a repeated ground bass launched by the continuo. This is the longest track at just over four minutes. It could be tedious but what with altering dynamics and a variety of articulation plus the gradually increasing virtuosity so brilliantly managed by Beyer this is a great performance. Track 10 is called an Aria but its happy compound time rhythm makes the continuo more into a ‘Giga’ in the shape of two guitars come into their own – here with no contribution from the violin. Track 21 is a ‘Movimento incognita’ in the French style. It has some of that “nervous introspection” Fourés mentions in his notes with its wild divisions on, again, a repeated bass. This is as long and as fascinating as track 2 mentioned above. Track 29 ‘Il Russignolo’ is just the opposite, being confident and dance-like. It moves into an imitative section (with the gamba and guitar) copying the song of the Nightingale. Track 39 ‘Aria for the flute’ is of course for the violin!

The recording is forward and yet natural and there is no ‘ecclesiastical’ sense of the monastic acoustic which if the photos are correct is a beautifully roofed room with artifacts and chairs and tables, – grand yet intimate.

So, although Matteis, whose dates incidentally are not quite correctly given, cannot be made out to be a forgotten genius, one cannot deny the fecundity of his art, his individuality and general influence on the period especially in England.