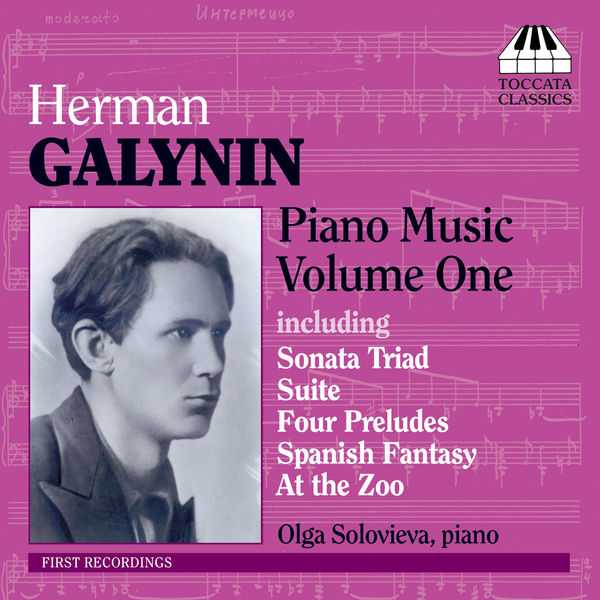

Composer: Herman Galynin

Performer: Olga Solovieva

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: Toccata

Catalogue: TOCC0076

Release: 2008

Size: 164 MB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: cover

Sonata Triad

01. Sonata No. 1 in B Minor

02. Sonata No. 2 in E Minor

03. Sonata No. 3 in B Major

Suite for piano

04. I. Toccata

05. II. Intermezzo

06. III. Dance

07. IV. Aria

08. V. Finale

4 Preludes

09. No. 1. Andantino

10. No. 2. Con moto

11. No. 3. Scherzando

12. No. 4. Lento

13.Waltz

14. Dance

15. Scherzo

16. Spanish Fantasy

The Tamer Tamed

17. Gavotte

18. Intermedio

19. Procession, “Bringing the Gifts”

At the Zoo

20. I. Siskin

21. II. Little Hare

22. III. Bear

23. IV. Swans

24. V. Elephant

The Russian composer Herman Galynin (1922–66) studied at the Moscow Conservatory with Shostakovich and Myaskovsky, producing a flow of brilliant compositions while still a student. They fuse influences from his teachers – Shostakovich’s wit and irony and Myaskovsky’s lyrical introspection – with Prokofiev’s rhythmic energy to produce a language very much his own. Although he was dogged by ill fortune (he was an orphan) and ill health, Galynin’s music expresses a defiant will to live with verve and humour. Herman Hermanovich Galynin (1922–66) met with his share of bad fortune, not least crippling illness and the hostile political climate of the Stalin regime. Galynin was born on 30 March 1922 in the industrial city of Tula, around 100 miles south of Moscow.

Orphaned at a young age, after surviving on his own for some time he was fostered in the orphanage at Tula only 14 years old, where his musical talents emerged. His musical gifts were held in the highest esteem by Dmitri Shostakovich and Nikolai Myaskovsky, his teachers at the Moscow Conservatory. Many of Galynin’s freshest works date from his student years at the Conservatory. Considered to be one of the casualties Stalin’s post-war cultural purges, Galynin was deeply affected by the dismissal of Shostakovich for harbouring ‘formalist’ tendencies. As a former pupil of Shostakovich, he was reassigned to a different teacher and asked to compose works to demonstrate his ‘re-education’ after having been ‘contaminated’ by Shostakovich. What remains most compelling about Galynin’s music is the highly personal quality of his lyricism, his ability to expand his material in fresh and fertile directions and a phenomenal rhythmic verve. All this is in evidence in his music for solo piano, of which this recording offers the first instalment of a comprehensive survey.

Like Arriaga — “The Spanish Mozart” — before him and Canadian composer André Mathieu in his own time, Russian Herman Galynin was a teen composer of considerable note. The core of the early part of his modest output was created before he reached the age of 18; the very idea of juvenilia seems to have been unknown to him, as by that time Galynin was producing fully mature and original conceptions. At the age of about 27, embittered and harassed by the Zhdanov purges and the public humiliation of his idol Dmitry Shostakovich, Galynin stopped composing. With one or two exceptions, that was about the end of it until he reached the age of 40 when he resumed and at 44, Galynin was felled by a sudden heart attack.

End of story, one might say, although in body he lasted a bit longer, in his creative life some might suggest that Galynin should join the so-called “27 Club,” the age at which certain rock stars tend to die. However, Galynin’s creative death did not occur at the end of a needle or a shotgun pointed the wrong way. Galynin was dealing with the interference of a ruthless and omnipotent government looking to control all aspects of cultural life and, as an orphan whose life was absorbed in music, he didn’t know much about the world outside of the Moscow Conservatory. Galynin’s course of study was interrupted twice, first by the German invasion during Operation Barbarossa and secondly in 1948 when he was reassigned to another professor in order to escape the “contamination” from Shostakovich. Galynin entered the Russian equivalent of a musical prep school in 1937 and the Moscow Conservatory proper in 1941. He did not graduate until 1950, and even as one of his toned down compositions subsequently took the Stalin Prize, Galynin remained stubbornly silent.

Until the appearance of Toccata Classics’ Herman Galynin: Piano Music, Vol. 1, Galynin’s silence has remained relatively secure. Although his Piano Concerto (1946) is a concert staple in Russia and well known there, and his few instrumentally conceived works recorded for circulation within the Soviet Union, only two of Galynin’s works ever made it to the West in the age of the LP. Many of the piano pieces heard here for the first time remain unknown even in Russia. They reveal a composer with seemingly inexhaustible youthful energy, a voracious appetite for musical styles, and a preference for clear, uncluttered textures. One might chalk that up to inexperience, but Galynin is extremely comfortable working in two or three parts, even in piano music. Sharpened by the sardonic wit of Shostakovich and Kabalevsky and gassed up by the example of Prokofiev’s propulsiveness, Galynin’s music has some measure of punk rock attitude. He chews up and spits out older forms like waltz and scherzo, tops Prokofiev with a machine-gun like Toccata played with maybe three fingers, and indulges in unrepentant blues harmonies in the Aria from his Piano Suite (1945). Apart from a couple of admittedly half-assimilated detours into Scriabin-esque territory, Galynin is always lean, mean, and on the scene. No wonder the Soviet Government wanted him so badly to behave.

Pianist Olga Solovieva, also known for her peerless advocacy for criminally underrated composer Boris Tchaikovsky, puts the best face on this Russian bad boy with crisp fingerwork and a joyous sense of abandon and forcefulness, yet never to the extent where her enthusiasm clouds the waters. Toccata’s recording, as is usual with piano solo recordings, is exactly right, bringing forth the sound of the instrument with all of its percussive touch and ringing tone where it matters most in this music. Anyone interested in twentieth century music — particularly that of Soviet Russia — will want to experience this.