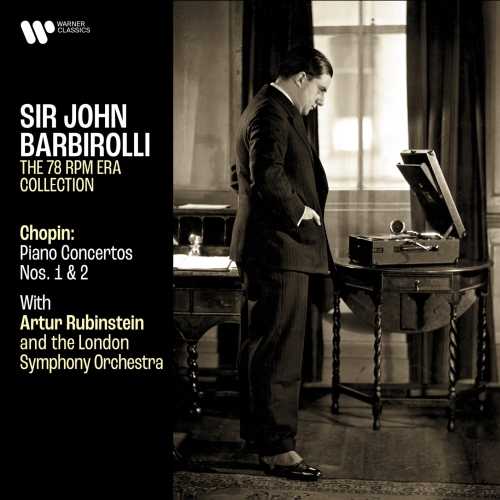

Composer: Frédéric Chopin

Performer: Artur Rubinstein

Orchestra: London Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: Sir John Barbirolli

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: Warner

Release: 2020

Size: 1.03 GB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: cover

Piano Concerto No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 11:

01. I. Allegro maestoso risoluto

02. II. Romanza. Larghetto

03. III. Rondo. Vivace

Piano Concerto No. 2 in F Minor, Op. 21:

04. I. Maestoso

05. II. Larghetto

06. III. Allegro vivace

Born in 1887, in the Polish city of Łódź, Arthur Rubinstein was the youngest of seven children, the sixth being born eight years before him. When young Arthur was four, Joseph Joachim tested his musical talent at Berlin’s Hochschule für Musik. He was not exploited as a child prodigy and returned to Berlin at the age of ten where Joachim supervised his musical training, and Heinrich Barth taught him piano. At twelve Rubinstein made his début in Berlin playing Mozart’s Piano Concerto in A major, K. 488, with Joachim conducting. The summer of 1903 was spent with Paderewski at his home in Morges and upon his return to Berlin, Rubinstein decided to finish his studies with Barth and go to Paris where he made his début in 1904. Two years later he made his début in New York and during the next ten years lived the life of a touring artist performing in Europe and South America and collaborating with Pablo Casals, Jacques Thibaud and Eugène Ysaÿe.

After the First World War, Rubinstein lived life to the full as performer and socialite, and continued a successful career well into his eighties. In the mid- 1950s he played seventeen works for piano and orchestra in five concerts, and in 1961, already in his mid seventies, played ten recitals at Carnegie Hall. He gave his final recital in London’s Wigmore Hall in June 1976 at the age of 87. He lived on with failing eyesight until the age of 95, completing two volumes of entertaining autobiography titled My Young Years (1973) and My Many Years (1980). He died in 1982 in Switzerland in Geneva.

Rubinstein had played both of the Chopin concertos right from the beginning of his career and they feature on his earliest surviving repertoire list of 1904 when he was seventeen years of age. Rubinstein recorded the Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor, Op. 21, the first that Chopin wrote, in 1931 with John Barbirolli and the London Symphony Orchestra. His second recording of the work heard here was made not long after the end of the Second World War in March 1946. At this time RCA was still recording on wax for 78rpm disc release, but also on lacquer discs, later transferred to tape for LP release. This accounts for the excellent sound quality of this recording made more than sixty years ago. Carnegie Hall was used as the recording venue and it took just over four hours to complete with most of the sections being recorded in first takes.

At the time of its release Harold Schonberg compared the recording to that of Cortot’s citing that Cortot ‘does not display the superficial brilliance that is so noticeable in Rubinstein’s set. The latter is too great a pianist to pass off with a mere shrug, but certainly he could have played with greater restraint and less of an impulse to exhibit the qualities of his fingerwork.’ Rubinstein certainly plays the scales in the dramatic section of the Larghetto in a rushed and perfunctory manner, but his fingerwork at the end of the third movement is not always clear where he prefers to concentrate more on rhythm and speed than articulation. An English reviewer wrote, ‘You might feel that there is an absence of quiet, delicate playing. He takes a dashing view of the concerto, of the first movement especially, and scarcely anywhere is there any pianissimo ravishment. But it is a valid view and this virile performance, with some wonderful playing, held my attention all through with delight.’ Rubinstein’s partner for the recording was William Steinberg (1899–1978) a German born American conductor who had studied with Hermann Abendroth at the Cologne Conservatory. He formed the Palestine Symphony Orchestra (becoming the Israel Philharmonic in 1948) with violinist Bronis1aw Huberman and was invited by Toscanini to become associate conductor of the NBC Symphony Orchestra, which he conducts on this recording. Rubinstein recorded this concerto twice more—in 1958 with Alfred Wallenstein and the Symphony of the Air, and in 1968 at the age of 81, with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra.

After the success of the 1931 Barbirolli recording of the Second Concerto, Rubinstein was paired with the same forces by HMV for his first recording of the Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Op. 11, in 1937. Rubinstein’s second recording of this concerto was made in 1953 with Alfred Wallenstein (1898–1983) and the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra of which Wallenstein was musical director from 1943 to 1956. Rubinstein had a very full day in the Hollywood recording studio on 12th December 1953. With producer Jack Pfeiffer in attendance, Rubinstein recorded some piano solos by Grieg, Schumann and Chopin beginning at 10.30am, breaking for lunch at 1.15pm for an hour and a half. Returning to the studio at 2.45pm he continued to record until 4.45pm. After a few hours break Rubinstein returned to the studio at 7pm where he was joined by the Los Angeles Philharmonic and Wallenstein where they worked for six hours, completing the recording session at 1am. Upon its release the recording was greeted with rave reviews: the American Record Guide began, ‘Here is another of RCA Victor’s stunning new recordings, and it mirrors with exceptional fidelity the loveliest performance of Chopin’s treasureable E minor concerto this generation has known.’ Another American critic concurred that ‘Mr. Rubinstein provides the best recording to date on LP of Chopin’s First Piano Concerto. The pianist personalizes the long, filigreed melodies with his perfect instinct for the right amount of rubato. The rhythms are free, never too free; the pulse relaxed, but not slack. The music breathes naturally; every little figuration can be heard to a proper degree. Strength and brilliance are available when necessary, and the Rondo is dashing, even playful. The piano is rightly given prominence in the recording, and it has a beautiful bright ring.’

A completely opposite opinion was expressed by an English critic who wrote a very anti-American review tetchily finding fault with everything about the recording and performance, at one point asking of Rubinstein, ‘Could he be persuaded to undertake a new recording in Europe?’ He found the orchestral playing ‘coarse-grained and raucous’ and continued that ‘Rubinstein has to play the second subject of the first movement and the melody of the Romance against what sounds like a prominent saxophone solo.’ One can only imagine that the reviewer had faulty or poor equipment, as this new transfer does not display any of these anomalies. One fact that is curious however, is the way Rubinstein plays the rhythm of the opening statement of the first movement. He does exactly the same in his 1961 recording with the New Symphony Orchestra of London and Stanislaw Skrowaczewski, but on his first recording of the work in 1937 plays it as it is usually heard and notated in the score.

Two American critics completely disagreed over Wallenstein’s support. The American Record Guide wrote, ‘Alfred Wallenstein, by the way, handles his part of the performance with unusual care and grace. He knows Rubinstein is the star of the occasion; but that does not embarrass him or keep him from providing alert support.’ In complete contrast another review of the same recording ended, ‘The only flaw in the performance is Mr. Wallenstein’s perfunctory reading of the orchestral accompaniment. Pale as the original scoring is, it deserves better treatment.’

These recordings of the Chopin concertos trade some of Rubinstein’s youthful exuberance found in his 1930s versions for a more coherent structural underpinning and improvement in sound quality.